Learning Anywhere and Everywhere

The idea of learning everywhere stood out to me in the Infinite Learning modules. To quote Michael Stephens (2016) on the shift away from in-person or place-based learning: “People expect to be able to work, learn, and study whenever and wherever they want to,” (p.124). I also like the idea that libraries promote all types of learning regardless of where the people they serve happen to be located (Stephens, 2012). As we approached the end of the semester, I became very aware of the different locations where I was working, learning, and studying. Because the MLIS program at SJSU is a virtual program, I have gotten used to being expected to complete my coursework anywhere and everywhere. I have been taking advantage of the shift towards distance learning and learning everywhere, from parks to libraries to cafes. I’ve spent enough time in my local Starbucks that I’m practically an honorary employee.

Balancing Library Spaces and Patrons’ Needs

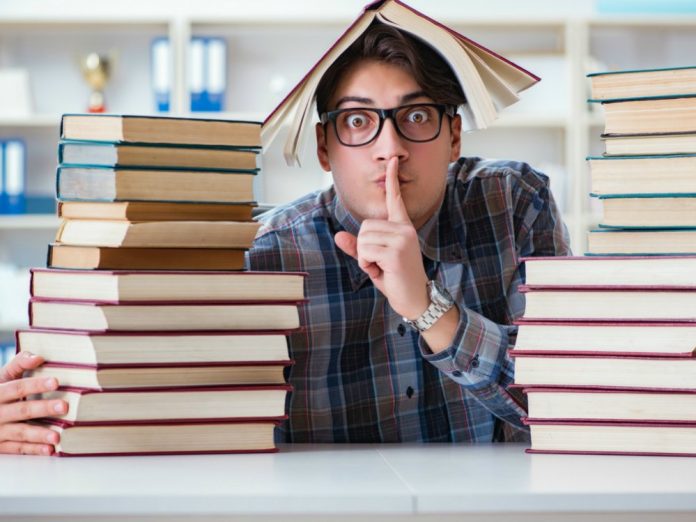

Libraries must respond to changing learning environments, not only to the shift away from placed-based learning but also to the shift towards collaborative learning environments. Libraries promote all types of learning regardless of where the people they serve happen to be located. Libraries are no longer just solitary spaces where patrons locate materials and read quietly. Instead, libraries are collaborative spaces that facilitate creative learning experiences (Stephens, 2016).

The question arises: how can libraries serve the needs of patrons seeking to use physical library spaces as places for completing independent work with the needs of patrons seeking collaborative learning experiences that require audible activities? People prefer different learning and working environments, and libraries need to create spaces that balance the need for quiet spaces and spaces where noise is acceptable and expected. Another question arises: how can libraries address space use conflicts and noise management? Libraries are responsible for balancing users’ differing needs and making the space as welcoming and practical for as many people as possible. However, addressing concerns and balancing needs can be challenging due to space limitations and existing designs (Jarson, 2018).

Image 1: The conflict between quiet and collaborative use of library spaces has library staff wondering, “To shh or not to shh?” (ITC, 2018).

I work at the San Jose Public Library’s Almaden Branch Library. One of my pet peeves with the design of this branch is the uneven distribution of quiet spaces with collaborative spaces. Patrons at this location frequently complain that there are not enough quiet spaces. There is one study room that can be reserved, but the room is in high demand. There is also a designated quiet room, but the walls are thin and noise from the children’s area and information desk penetrate the walls. We try to enforce consistent policies surrounding noise and accommodate patrons concerned about noise to the best of our abilities. Still, I know firsthand that from a library support staff perspective, it is challenging to balance the needs of patrons in a shared space. I am curious to learn more about the potential solutions other libraries have implemented in addressing the needs of multiple users.

References

ITC. (2018, May 1). To Shh or Not to Shh That is the Question. Retrieved May 12, 2024, from https://inthecove.com.au/2018/05/01/to-shh-or-not-to-shh-that-is-the-question/

Jarson, J. (2018, April 8). What is library space for?: Reflecting on space use and noise management. ACRLog – Blogging by and for Academic and Research Librarians. https://acrlog.org/2018/04/08/what-is-library-space-for-reflecting-on-space-use-and-noise-management/

Stephens, M. (2012). YLibrary? Making the case for the library as a space for infinite learning. https://www.dropbox.com/s/p46kkmbkvwpdsng/YLibraryInfiniteLearning.pdf?e=1&dl=0

Stephens, M. (2016). The Heart of Librarianship: Attentive, Positive, and Purposeful Change. American Library Association.