I feel like The New York Times summed up the entire history that led to this class in one sentence: “Curators 35 years ago were not interested in what the public needed — they were interested in what the curators thought the public should have.” For those of us who grew up in that environment, I’m not sure that asking will help – we the public do not necessarily know what we want until it is handed to us, at which point it becomes unacceptable to not have that thing, much like a smart phone or wi-fi.

There is an ever-widening digital divide occurring between GLAM organizations that have embraced technology and those that have not, but if one were to ask me – an educated but not particularly interested in art person – what I would want from my local museum in order to bring me in the door, I do not know what I would tell them: “Um… get more interesting stuff? Maybe famous stuff I have heard of before?”

Which begs the question: Why have I heard of some art but not others?

Which opens the floodgates.

During my BA, I did an involuntary cognate in Art History that was required by my major. In those courses, I was told the stories of art. I learned the soap opera that was the life of the artist. I learned about the incredibly specific techniques used to create the art, and how each artist built on the work of their predecessors to create something new and exciting. I learned about the controversies that surrounded the exhibition of these pieces. In those lectures, the pieces – that would otherwise have been “yep – that’s a tree/statue/soup can” became set pieces on the epic stage that is history.

The works of Dan Brown are greatly maligned by the literary community, but viewing art and architecture in Rome or Paris or London after reading those books hits differently than before. The context changes the perception.

A friend has a different perspective. He is not a story person. He plays expansive MMORPGs and has absolutely no idea what is happening between NPCs. (It is maddening.) For him, he could not care less about the artist or the patron. When he goes to an art gallery, he “looks at the pretty pictures.” What does strike him, though, is the process of making photo-realism from paint or marble. He would love to see the process in layers, rather like the time-lapse videos on social media. [Watch this on double speed with the sound off to get an idea of what I mean.]

There are incalculable variations on this theme, but it boils down to these two points: Context gives meaning to the meaningless, and there is no one-size-fits-all answer to “What do people want?” There is only “more.”

Remember the interactive science museums of our childhoods with the handles to crank and the circuits to connect? What if we used the new technology to make all museums as interactive? Gamify the GLAM experience. Use the art as the basis for scavenger hunts, with quizzes and badges to earn along the way. Market them to everyone, not just children. Adults like games too. Ensure repeat visitors and creative use of the space by making badges collectable over years. Use the experience of the old docent-led tours to point viewers along the path of the museum, stopping at specific pieces that tell one cohesive story, rather than leaving it up to the patron to choose random pieces about which to learn. (Ensure that by the time one collects all the badges, they will have seen everything.)

Visitors inside the Sistine Chapel

Use the VR experience in places where one cannot actually see the art. The Sistine Chapel in the Vatican City is one of the most visited pieces of art in the world, but it is also 68 feet in the air. Imagine a VR experience where one could examine individual portions at leisure while also hearing the story of Michaelangelo’s endeavor and his relationship with Pope Julius II or seeing a ramped dramatization of the process.

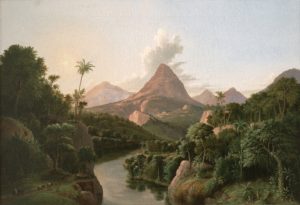

CROSSING THE ISTHMUS, CIRCA 1858.

Albertus Del Orient Browere (American, 1814–1887)

Oil on canvas, 33 x 44 in. Crocker Art Museum Purchase, 1984.8.

The Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento “was the first public art museum founded west of the Mississippi, established in 1885.” According to its website, it houses “the state’s premier collection of Californian art, dating from the Gold Rush to the present day,” but without additional context, that painting by Albertus Del Orient Browere is just a hill in Panama. I have no idea why it is in a museum as opposed to someone else’s of a still life of fruit. Place it next to a piece that would never be put in a museum on the app; show me the difference between “art” and “trash.”

According to the Our Museum report, one of the biggest concerns is fear: “But what if we implement all of these changes and they don’t work?” or worse: “What if we waste all the money on a losing proposition?”

When dealing with limited finances, the fear of failure — of wasting precious resources — is a huge barrier to creation. As much as it seems counterproductive, we have to build in an expectation of failure. In science, failure is the norm. Even when something is a success, it must be replicated over and over before it is trusted. We have to set aside the necessity of immediate gratification and consider each minute participatory activity as a building block not of a program but as a piece of the much larger puzzle that eventually says, “The GLAM organization is the place where the things happen.” Maybe you try the Smartify app, but you realize that it only really works outside because the building has terrible cell service or there are too many people using the wi-fi (think the Louvre at capacity). Maybe the Beacons that use Bluetooth inside are too affected by the crowds around certain objects. That is okay – there is bound to be a return policy, or another organization who could use them. The app that failed at the Crocker could be repurposed for the Wide-Open Walls project that creates murals throughout downtown.

Raphael Delgado: California Bear (2017)

If you tried to put together a puzzle but you were afraid to place the first piece because it might not be exactly right, how far would you get? “We acknowledge that any large-scale organisational change takes at least five years – and at least that long before we know if it really is succeeding.” Unless there is a sudden social-media viral response to something (we can only dream), it will take ages before people change their opinions, before all the people who attended and were disappointed can be convinced to come back and try again. The important part is that the organization is seen to be doing something. Even if it wasn’t wholly successful the first time, patrons will check back to see what is happening now. “Maybe this time, it will be something I like.”

@jeanna I so appreciate this post regarding museums and interactivity and technology. I have really enjoyed some of the museums I’ve visited in the last couple of years, including those in Scotland, and in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Both utilize technology in interesting ways, and they also told stories via the exhibits, artifacts, etc. Innovation in the museum sector continues, especially with what I see going on in some art museums with displays and immersive environments.