What I find most fascinating about radical trust is how it challenges the traditional boundaries that most libraries have operated within for a very long time. Throughout my life, I’ve only known traditional libraries with the “for books, not necessarily for people” mindset. However, I am excited to learn about libraries shifting away from this attitude to actually become more than just a place for books, but rather a third space for anyone to explore, create, and thrive within independently. That’s a whole new world to me!

Lending Beyond Books

Raymond Village Library. Sourced from The Windham Eagle (n.d.).

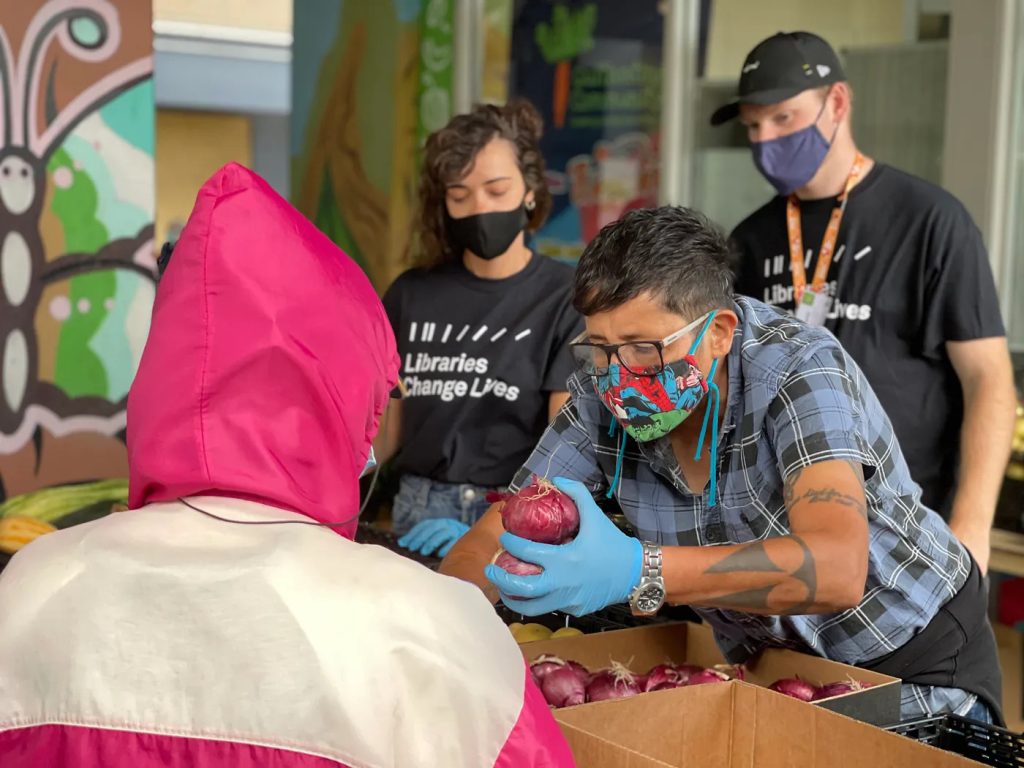

Radical trust in libraries is a philosophy that emphasizes deep confidence in patrons’ ability to use library resources and spaces responsibly (Ashikuzzaman, 2024). As libraries evolve into community hubs offering much more than just books, they rely on this trust to successfully provide new services. An example of this would be the lending of non-traditional items like pots and pans, toys, tools, knitting kits, or fishing poles in regions like the Honeoye Library in the Finger Lakes, where people fish year-round (Blair, 2013). By enabling users to take ownership of their library experience through a newfound sense of accountability, libraries can actually transform into dynamic community hubs. By doing so, their patrons will feel more valued and more likely to actively contribute to the library’s future success and prosperity (Ashikuzzaman, 2024).

Creating Dynamic and Inclusive Spaces

Radical trust can also be found within the implementation of programs such as makerspaces. In these programs, users are often given access to expensive equipment or digital resources requiring proper care and safekeeping, while they explore various emerging technological tools like digital cameras (Stephens, 2010). However, how is one to know if they have any interest in, let’s say, photography or filmmaking without access to the right tools necessary for the endeavor? Trusting one’s library to provide access to such high-end equipment through the means of makerspaces allows users to actually know if a particular hobby will stick before spending loads of money on such expensive gear (Griggs, n.d.).

3D Scanning at the Castlewood Makerspace. Sourced from the Arapahoe Libraries (2023).

Building Trusted User-Centered Services

As librarians, it is essential for us to trust our users to responsibly manage borrowed items and respect library spaces. Through this trust, we can build a positive atmosphere where patrons view the library as a collaborative space rather than a restrictive one, thus strengthening the relationship between the institution and the community. By trusting them, we will be able to reduce unnecessary barriers and truly improve their user experience, as well as our own. An example of this mutual sense of trust and respect can be found with the rise of self-checkout services.

SFPL Book Stop on Treasure Island. Sourced from SF.gov (2023, March).

One notable example of such radical trust in action is the implementation of self-checkout systems, like the San Francisco Public Library’s first book kiosk, the SFPL Book Stop, which not only reduces the need for staff intervention but also allows users to manage their borrowing activities independently. The success of self-checkout systems is evident in their widespread adoption and positive user feedback from those who appreciate the increased control over their borrowing practices as they waste less time standing in long lines at the circulation desk (Bibliotheca, n.d.).

Balancing Trust with Structure

However, trust does not mean a lack of structure. Clear guidelines and education on proper usage of these resources are essential to maintaining a healthy library-user relationship. Just as @Michael mentioned in The Transparent Library 2 (2007), rather than timidly avoiding patrons misusing library resources, our focus should remain on open communication and the continuous reinforcement of existing policies in lieu of banning the trusted service due to a few unpleasant users breaking the rules.

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez. Sourced from Unsplash (2018, April).

Reflection

As a future information professional, incorporating radical trust, for me, involves examining and addressing my own mental limitations and trust issues. Having witnessed others damaging resources or misusing library services in the past, unfortunately, I’m uncomfortable placing confidence in others’ ability to act responsibly without my close supervision. I even feel this way towards some family members. However, I realize this mindset is damaging to all, including myself, and can strongly limit any potential for innovation and community engagement. Moving forward, I will have to address these personal barriers in order to create an open and participatory environment where users are truly empowered to take ownership of their experiences within the ultimate library space.

References

Ashikuzzaman, M. (2024). Community engagement in libraries. LIS Education Network. https://www.lisedunetwork.com/community-engagement-in-libraries/

Bibliotheca. (n.d.). Why self-checkout is a game changer for libraries. https://www.bibliotheca.com/insights-trends-why-self-checkout-is-a-game-changer-for-libraries/

Blair, E. (2013). Beyond books: Libraries lend fishing poles, pans and people. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2013/08/13/211697593/beyond-books-libraries-lend-fishing-poles-pans-and-people

Casey, M., E. & Stephens, M. T. (2007). Ask for what you want. In The Transparent Library 2. Library Journal. https://tametheweb.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/TheTransparentLibrary2.pdf

Griggs, M. B. (n.d.). Libraries are great at lending all sorts of things—not just books. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/checking-out-tools-and-telescopes-local-libraries-180952662/

Schmidt, A. (2013). Earning trust: The user experience. Library Journal. https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/Innovation/earning-trust-the-user-experience

Stephens, M. T. (2010). The hyperlinked school library: Engage, explore, celebrate. Tame The Web. https://tametheweb.com/2010/03/02/the-hyperlinked-school-library-engage-explore-celebrate/