image credit: Adobe Firefly AI Image Generator

I was taken by Professor Stephen’s definition of Technolust as, “an irrational love for new technology combined with unrealistic expectations for the solutions it brings” (Casey & Savastinuk, 2007; Stephens, 2008). This idea underscores the vast changes from the last thirty years in libraries. Specifically with the promises of ebooks and digital items to expand access, reduce costs, and provide remote access.

Buckland (1999), wrote in Redesigning Library Services: A Manifesto, that digital items could be beneficial when the item is volatile, requires manipulation, needs to be scanned (read: ctrl+f) for names and words, to provide remote access – and to greatly increase communication speed. These benefits were laid out in 1999, when electronic card catalogs and electronic document possibilities propelled libraries into exciting directions. Buckland also writes that, “a digital record is more economical and, ordinarily, more useful” (Buckland, 1999). In my notes I wrote in the margin, simply, “is it though?” I decided to research the forecasted benefits of electronic content from almost thirty years ago and contrast that with what I see working in an academic library.

eBooks and Academic Libraries

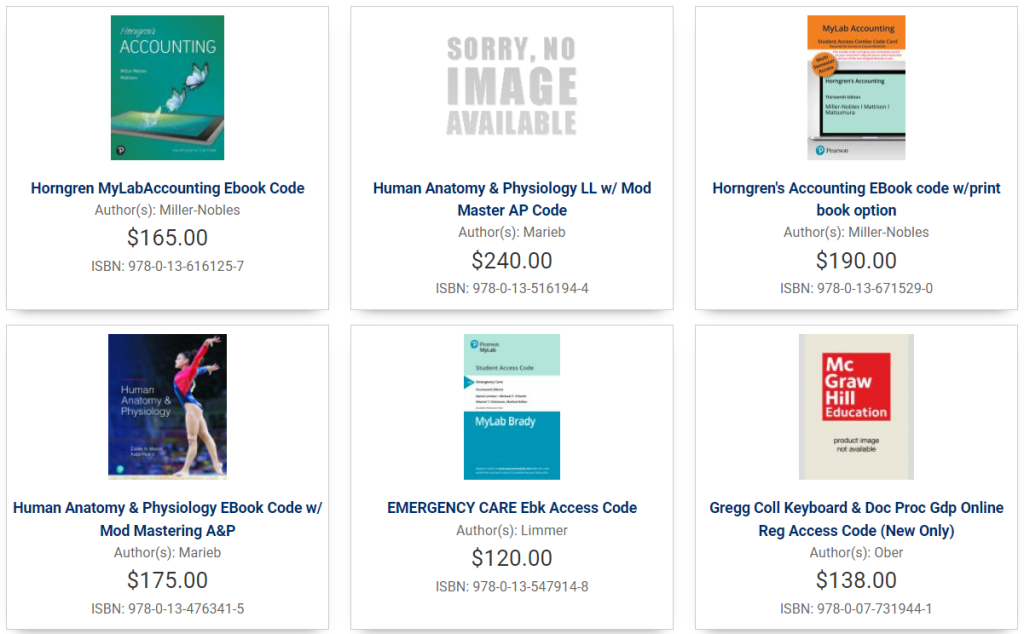

Academic libraries have embraced ebooks and digital collections and do so with the hope that they will be more accessible, cheaper, and quicker to deploy. Purchasing an ebook highlights the “just in time” service model. For example, at the community college where I work we’ve had students ask for materials and we can trigger an ebook version in a database subscription to provide access almost immediately. But questions remain about if this embracing of technology, bordering on the technolust of “look how fast and economical we are”, considers what users want. Also, we’ve encountered requested digital titles that are several hundred dollars per license and have many restrictions. Academic libraries are also seeing more textbooks move to redeemable ebook codes that I like to call the “gift card-ization of textbooks”. The code may only be used once and eventually expires, which means it is actually a book rental.

Below is an example of college textbooks from a community college bookstore that illustrates ebook formats do not necessarily make textbooks inexpensive, a hope for digital content from a few decades back.

Academic eBook Textbook Pricing

Research Says …

A study creatively titled, “Do you love them now? Use and non-use of academic ebooks a decade later” found there are many new challenges with ebooks such as licensing that restricts to one user at a time, limits how much of the ebook may be printed or downloaded, navigation difficulties, and the inability to take notes (Owens et. al., 2023). There were also concerns about ebooks supporting different learning styles or being accessible for those with disabilities. Owens, et. al. (2023) also found that the increase in ebook purchasing due to providing service during COVID-19 did not improve perceptions of ebooks among students and faculty. Eye strain, headaches and other issues were concerns from students as well (Casselden & Pears, 2020). Another consideration from these studies is that students preferred print books for particular subjects – for example if a book requires moving back and forth to reference information.

Reflection

Considering technolust and digital book formats informs my library practice in so many ways. The biggest takeaway is remembering that is there is no one size fits all. Are we practicing our hyperlinked goals of including our entire campus community in library services? These hyperlinked concepts also take me back to what I have learned about information communities. I need to remember to center what our users tell us they really want. Also, to remember that we can influence what services are offered by vendors by voting with our budget dollars.

Here are a few specific things we can do to improve student access to information and course material in digital formats:

- Make purposeful choices when purchasing ebooks, such as, is the only option a “single user” ebook title, or is there an unlimited access option?

- Pay attention to printing and download limits and opt for the most open format available.

- Become a campus-wide advocate for Open Education Resources (OER) – free textbooks that faculty may remix, reuse, and offer as a free PDFs, such as OpenStax.

- Communicate honestly with vendors about why we aren’t purchasing their content.

I feel that we must ride both waves – give in to the technolust while at the same time remember to pull back and focus on what best suits our users.

References

Buckland, M. K. (1992). Redesigning library services : a manifesto. American Library Association.

Casey, M. E., & Savastinuk, L. C. (2007). Library 2.0 : a guide to participatory library service. Information Today.

Casselden, B., & Pears, R. (2020). Higher education student pathways to ebook usage and engagement, and understanding: Highways and cul de sacs. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 52(2), 601–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000619841429

Owens, E., Hwang, S., Kim, D., Manolovitz, T., & Shen, L. (2023). Do you love them now? Use and non-use of academic ebooks a decade later. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 49(3), 102703-. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2023.102703