Hello! I was hoping to embed my symposium, but the file was a little too large. So here’s the Google Drive link to my 5 + 1 symposium!

December 9, 2025

Innovation Strategy & Roadmap: Bring Your Own Book Club

Hello! Here is the Google Slide link to my Innovation Strategy & Roadmap presentation: Bring Your Own Book Club!

December 9, 2025

Inspiration Report: An Academic Open Library

Hello! Here is the Google Drive link to my inspiration report: An Open Academic Library by Michelle Peralejo

December 7, 2025

Learning Beyond our Books

In my first reflection post, I referenced my generation’s relationship with technology and how quickly technology is evolving now. Not only must we learn new technical skills, we must understand the potential use cases for our patrons and the nuances of digital life. (For example, it is one thing to understand how to fill out an online job application, it’s another to be aware of what recruiters look for on the resume.) It’s especially important to practice as information professionals. At the very least, we need to stay updated in order to provide accurate information to our patrons. We also can set the example, demonstrating how to pursue lifelong learning at any stage of your life, even when you are already professional!

I appreciated the Medium article on the breakdown of digital intelligence. I’m used to being the tech-savvy person in my family, but this article reminded me that digital intelligence is expanding alongside technology and that infinite learning applies to myself, in both the personal and professional context. The article was geared towards teaching children, but everyone can benefit from a refresher computer class. Fostering a culture of infinite learning includes meeting everyone at their level, and libraries can provide that education environment without the same age restrictions and expectations as a traditional classroom.

It’s also clear that libraries provide more than just structured educational opportunities. Kenney’s article on the reference in the modern library shows that librarians also help patrons apply that knowledge, usually with tasks needed in daily life. This type of role requires more on-the-go thinking and dynamic communication skills then typical classes. As Kenney pointed out, this reality has “unclear expectations,” but the silver lining is that this is occurring across libraries. Librarians can learn from each other and their experiences to navigate these changes. Just like technology, the opportunities for collaborating and ever evolving and can take us to new heights.

Citations

Kenney, P. (2015, September 11). Where Reference Fits in the Modern Library. Publishers Weekly. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/7nmpo0n5k5cn7x4nrfs1u/Where-Reference-Fits-in-the-Modern-Library.pdf?rlkey=5ifp67t3sl7jhazw2mmhe78ew&e=3&dl=0

Park, Y. (2016, June 4). 8 digital skills we must teach our children. World Economic Forum. https://medium.com/world-economic-forum/8-digital-skills-we-must-teach-our-children-f37853d7221e#.789qtaw64

December 7, 2025

A Space for All Stories

I’m always comforted when I walk into my local library and spot what books are on display each month. From the rainbow pride display in June to indigenous literature featured in November, it’s heartening that highlighting books by and about underrepresented identities and communities have become more mainstream on social media, in everyday conversations, and in public libraries.

Stories have always been a (relatively) safer way to reflect on different thoughts, histories, and lived experiences, so diversifying the stories we listen to is an opportunity to expand our perception of the world and other people. I say “safer,” but I don’t mean it is or should be a frictionless experience. In conversations about championing diverse books, some people have commented that reading stories and practicing empathy and cultural competency in real life are still two different acts. I agree that how we participate in these stories influences what we take away from them. Reading a book in isolation can lead to staying within our comfort zone, away from challenging our biases or fears of learning something new.

In contrast, the Human Library is inherently participatory, emphasizes face-to-face conversation, and encourages active listening and human connection. It also further demonstrates how the library goes beyond “physically” keeping stories in a building. Librarians can show that we actively recognize the value of these stories, will connect people to finding these stories, and will support people throughout the creation and development of these stories.

As Mark Ray highlighted, the Human Library is only made possible by the people volunteering to share their stories and participate as human books. This decision can be a very vulnerable experience, and the librarians heading this project would also need the emotional intelligence and cultural competency to guide the volunteers through that process of developing their presentations. I feel it’s significant to point out that the majority of the traditional publishing industry is white and favors publishing white authors. There is representation lacking on both sides. While libraries are absolutely part of advocating for representation in that space, but our role in knowledge creation also extends to creating a space where underrepresented stories and their authors are fostered and valued. We can say, “If you do not hear your voice anywhere else, you will be heard here.”

Citations

Jiménez, L. M., & Beckert, B., Polera, R., & Dietiker, J. C. (2023). The Lee & Low Diversity Baseline Survey 3.0. Lee & Low Books. https://www.leeandlow.com/about/diversity-baseline-survey/dbs3/

Ray, M. (2019, April 12). Courageous Conversations at the Human Library. Next Avenue. https://www.nextavenue.org/courageous-conversations-human-library/

So, R. J., & Wezerek, G. (2020, December 11). Just How White is the Book Industry? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/12/11/opinion/culture/diversity-publishing-industry.html

December 7, 2025

Wellness and Resistance in Libraries

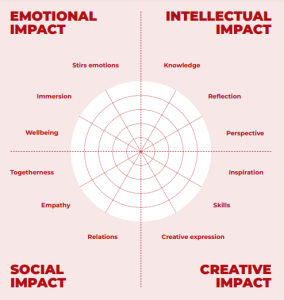

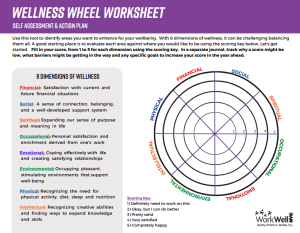

When I first saw the impact compass (developed by the Roskilde Central Library and Seismonaut), my brain immediately thought of the wellness wheel assessment tool. On the surface, they are both radar charts used for assessment and guidance on areas of improvement. I think the association between library impact and wellness is appropriate; some dimensions already overlap between the charts, and we can see how the library can feed into the other dimensions of wellness.

I wouldn’t suggest formally combining the two assessments, but reframing libraries and the work we do as influential and in pursuit of wellness is morale-boosting (in my eyes, at least). The impact compass works as a qualitative tool for libraries, and I can also see it prompting deeper reflection for librarians and library users. While there may always be a bureaucratic imperative for collecting quantitative data, simply reading the 4 dimensions of the compass prompts you to think of your memories and emotions toward the library. I would hope that in my career, the people I help remember any feelings of joy, pride, and connection they experienced at the library, over than simply tracking how many times they’ve visited. We can also tell a more complete and accurate story of the work we accomplish through the lens of our impact.

libraries have become a crucial part of the safety net, the educational system, and the local democracy as well…

However, understanding the library’s impact and the narrative we develop is only one part of advocating for new designs and mindsets about what the library can do. In his interview with CASBS, Klinenberg answered that decisionmakers that fail to see the value of libraries are the reason that some programs and policies to make the library more accessible fail. I agree that there are people that see the library as an outdated institution that revolves just around books, and that it is our responsibility to advocate and change that perspective. However, I also believe there are decisionmakers decreasing access to the library precisely because of its importance to our educations, local democracy, and communities as a whole. Citizens who are educated, engaged with their community, and have access to some basic needs know why and how to fight for a better future. I think recognizing this aspect of our work is also crucial, both as a reminder on why to advocate and to better connect us with the people we serve.

Citations

Gaetani, M. (2018, November 11). Q&A with Eric Klinenberg. Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. https://casbs.stanford.edu/news/qa-eric-klinenberg

Lauersen, C. (2024, August 25). The value of libraries from Roskilde to Toronto. The Library Lab. https://christianlauersen.net/2024/08/25/the-value-of-libraries-from-roskilde-to-toronto/

WorkWell NYC. (n.d.). Wellness Wheel Worksheet. WorkWell NYC. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/olr/downloads/pdf/wellness/wellnesswheelworksheet.pdf

October 13, 2025

Keep Calm and Read Banned Books

When I was growing up, parents and teachers often warned that once something is posted on the Internet, it would stay there forever. As an adult, I better understand that this assumption that online or digital records are automatically preserved is complicated by the financial, legal, and technological logistics of digital storage and access.

For librarians and archivists, digital permanence is a part of our professional responsibilities. But we also have the responsibility to avoid any assumptions of our authority and objectivity over digital archiving and preservation. In Becerra-Licha’s article on post-custodial archives, she explains how we should interrogate how archives can leave communities and histories behind and turn it into an opportunity to create participatory, community-involved archives that also prioritize consent and privacy (2017). I have personal and professional interest in archival work, so I appreciated seeing how non-archivists can and should be involved in archival work.

However, I cannot talk about preserving documents without also acknowledging the ongoing issue of censorship and book challenges. Physical and digital media are still in danger from these censorship attempts. The discussion of this issue prompted many emotions and self-reflective moments for me. Watching the videos on the book challenges and reactions in Michigan and Texas, I found myself feeling discouraged, anxious, and furious to see both libraries/librarians and the queer community (of which I’m a part of) in the crosshairs of censorship and discourse over what is “child-appropriate.”

A part of my uncertainty and anxieties do stem from the fact that I do not currently work in a library and have not dealt with book challenges professionally. When I do start working in libraries, how will I respond? The majority of book challenges are happening in public libraries; should I lean towards public librarianship for my career because of these challenges? How would I support my professional peers if I’m in a different sector?

Graphic from the ALA, breaking down where book challenges take place

Thankfully, the increase in book challenges also means a strong, ongoing response from librarians and advocates. (In fact, this reflection is posted right after Banned Books Week 2025, so there are ample resources on how to advocate for our “freedom to read.”) Libraries are part of their communities, and this includes how we connect with local policymakers and can invite and guide communities to advocate with us. I’m heartened when I hear that in every story of a book challenge, there are groups of non-librarians showing up and advocating for us and the communities the books represent. In both archives and libraries, there is no better opportunity to invite people of diverse identities and communities to get involved. Digital and online platforms also provide many different ways to participate, from citizen archivist work to involving teens and young adults at the public library to posting your support on social media.

Header graphic for Banned Books Week 2025

Citations

ALA. (2025). Free Downloads | Banned Books. https://www.ala.org/bbooks/bannedbooksweek/ideasandresources/freedownloads

Becerra-Licha, S. (2017, October 23). Participatory and Post-Custodial Archives as Community Practice. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/10/participatory-and-post-custodial-archives-as-community-practice

Center for International Scholarship in School Libraries. (2022). Banned Books Survival Guide. https://comminfo.libguides.com/BannedBookSurvivalGuide_548_FL22/Home

CNN. (2021, Decemeber 21). Librarians fight back against push to ban books from schools [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M88WuMRNxoU

MLive. (2023, May 18). ‘Gender Queer’ and the culture war in Michigan’s libraries. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x043zuGWgMA

October 6, 2025

A Library is… the Statue of Liberty?

Ciara Eastell began her TEDx talk by describing two libraries, the Exeter Library and the Ferguson Public Library, that stayed open amidst harrowing and somber conditions to become an oasis for visitors. My mind immediately went to the poem attributed to the Statue of Liberty, the hope of accepting and welcoming everyone.

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

–Emma Lazarus, The New Colossus

Eastell also shared data on the perception of libraries as a safe space for their communities. Libraries provide access to free shelter, resources, and services to support, inspire, and educate any visitor. And if the library cannot provide that outright, it will connect visitors to other community resources that can. I’m lucky to be surrounded by friends and family who participate in and appreciate their libraries, and contribute to my understanding of what I am capable of achieving for our communities. My family members remember libraries as a safe space to quietly study when you live with a large and loud family, to apply for jobs when you’re newly immigrated and can’t afford a computer, to bring your kids when everywhere else is too expensive.

Still, a part of me remains hesitant to be optimistic about libraries working toward diversity, inclusion, and equity to fully serve their communities. Librarians are just as human and influenced by unconscious biases as anyone else. When I just started this program, I learned that the majority of ALA members were white, middle-aged, able-bodied women (according to ALA’s Demographic Study Report in 2017). I had to reckon with the fact that I would be the minority in my own future field.

Additionally, librarianship is not immune to ugly histories nor critique thereof. In Fobazi Ettarh words, “Librarianship, like the criminal justice system and the government, is an institution. And like other institutions, librarianship plays a role in creating and sustaining hegemonic values,” (Vocational Awe and Librarianship, 2018). Ettarh also wrote on the job creep many librarians experience; when libraries do commit to fulfilling a specific social need, it can place a heavy, unexpected responsibilities on those on the frontlines. Is there a way to continuously serve the community while safeguarding everyone’s wellbeing?

There are never any easy answers, but there are actions we can take to move forward, which include acknowledging when our history includes censorship and discrimination. I appreciated Lauersen’s reflections on inclusion and the sheer effort it takes to enact change, especially because he reflected on his own privilege and biases. Likewise, self-reflection, unlearning biases, and developing cultural competency are all steps forward. Beyond this, I know my personal and professional life is dependent on sitting with discomfort, from acknowledging how my biases influence my behavior to being nervous with public speaking, and using it as a jumping off point for growth and action.

Citations

Ettarh, F. (2018, January 10). Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves. In the Library With The Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2018/vocational-awe/

Lauersen, C. (2018, June 6). Do you want to dance? Inclusion and belonging in libraries and beyond [Keynote address]. UXLibsIV, Sheffield, England, United Kingdom. https://christianlauersen.net/2018/06/07/inclusion-and-belonging-in-libraries-and-beyond/

TEDx Talks. (2019, June 13). How libraries change lives [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tvt-lHZBUwU&t=330s

September 20, 2025

The Times (and Tech) They Are a-Changin’

When I began the Foundational readings for the Hyperlinked Library, the snapshot it created of Library 2.0 was an emerging concept and technology of the early 2000s. For example, Buckland’s specific technological references include “computer-based operations” becoming more affordable and storing “library materials in electronic form” (1993). Speaking as someone from the generation of grew up with Web 2.0, it’s strange to consider how common such things are nowadays. Others references in the text described the early days of libraries buying books from Amazon and user participation on the web stuck out to me because technology and our relationship to it has drastically evolved since the publication of the texts. Even the most recent publications were published before the COVID-19 pandemic, which is still impacting our everyday experiences and (user) needs.

Initially, I felt overwhelmed by how fast and dramatically some of the technological details no longer apply (or have exceeded our initial expectations). How could we as librarians ever hope to keep up? But sitting with that question only reinforced another core feature of the hyperlinked library: continuously embracing and implementing change for the good of the libraries and their users.

Change Involving Everyone

Within the model of Library 2.0, “constant and purposeful change” in libraries is inherently tied to centering and inviting library users into the redesign process (Casey & Savastinuk, 2007). What the change actually looks like will ultimately be defined by the user needs and how the librarians (and staff and volunteers and administration) meet that need. While involving users into this creation is no longer novel, this can come with its own set of challenges. Borrowing lessons from the design thinking process, evaluating user needs in practice could include:

- interviewing users directly and empathetically

- observing users’ behavior in the library and non-verbal reactions

That being said, creating change oftentimes also requires people and organizations to change themselves. I resonated with some of the barriers and mindsets that Stephens described as “holding librarians back” like being stuck in the mindset of “this is how it’s always been done” and feeling like there would be no time, support, or financial resources to implement change (2016). In my current administrative job, I’m one of the newer, younger employees, and my initial belief was that there were long-held processes in place, and that my job was to learn and assimilate to them, not to rock the boat.

With time and more working experience (and some inspiration from the Foundational readings), I learned that self-confidence, advocacy in the workplace, and empowerment from the organization are key for both productivity and progress. As such, implementing changes for our users and implementing changes in the workplace and design process will have to be done in tandem.

Lessons to Take Forward

The inevitability of change can be a hopeful, optimistic sentiment. So often, we feel that change is out of our control. We either feel that it is happening to us without our permission, or we feel disempowered to implement truly lasting, helpful change. But if technology has changed so much that what was once emerging is now mundane, then there is hope that our efforts today becomes tomorrow’s normal. The services offered by libraries, the technology we use, the mindsets that hold us back–we’ve changed them before, and we can change them again.

We get to decide what change looks like in our libraries. I started this post by saying how overwhelming rapid technological change could be. But the details of technological changes are only as important as how they inspire users and fulfill their needs. The sheer range of what libraries look like is evidence for this. Depending on the users, they may want to keep spaces filled with physical books (even with easy access to electronic alternatives) or designing maker spaces with tools fitting the study programs of university students. As long as we empower ourselves and listen to our users, we are in charge of the positive change we implement.

Citations:

August 25, 2025

Introduction

Hi, everyone!

My name is Michelle, and this is my third year in the MLIS program! I’ve lived in SoCal my entire life, attended UCLA for undergrad, and have an English B.A. I’ve loved visiting my local library since I was young, but it was only during college that I decided to pursue librarianship, as it matched my values of community, accessibility, and lifelong learning. I’m so excited to learn the intersection of emerging technology and connecting with library users. And to meet and learn with all of you, of course!

Outside my office job and school work, I enjoy discovering new graphic novels, watching Dimension 20, and taking care of my pixelated farm in Stardew Valley. WordPress is not my first blogging experience (shout out to all my fellow Tumblr veterans), but I’m eager to personalize this blog. Speaking of, my site URL is trying to evoke the idea of a train station! Partly because I commute via public transit every day, and partly because I like that both stations and libraries are spaces meant to connect different places and people to each other.