The open-air amphitheater of the Salt Lake City Library is a central hub for gathering and hosts free performances and programs.

Image source: Safdie Architects

I have been putting off writing this blog post because, I’ll be honest, reflecting on the future of libraries and library work has had me in a bit of a tailspin lately. The fatalistic part of me thinks that the future, in general, feels so unstable, and libraries, more specifically, feel doomed. As Eric Klinenberg says in his book Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life (as quoted in an interview with Gaetani, 2018):

“social order now feels precarious” and our “collective project is in shambles.” Ultimately, “the stystems we build in coming years will tell future generations who we are and how we see the world today. If we fail to bridge our gaping social divisions, they may even determine whether that ‘we’ continues to exist.” (quest. 4)

As I think about how libraries impact our society – and what might happen if we were to lose them – my thoughts turn to the idea of community and “third places.” A “third place” is a social environment that is separate from the predominant two social settings in humans’ lives: the home (first place) and the workplace (second place). The term was coined by sociologist Ray Oldenberg in his 1989 book The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (second edition published in 1997), in which he describes “happy gathering places…’homes away from home’ where unrelated people relate” (p. ix).

What Makes a Third Place?

Oldenburg defines third places by eight generally-shared characteristics:

- Neutral Ground: participants have no obligation to be there – financially, politically, legally, or otherwise – and are free to come and go as they please;

- Leveler: third places put no importance on an individual’s status in society, and there are no prerequisites or requirements for participation;

- Conversation: playful conversation is the main focus;

- Accessibility & Accomodation: third places must be open, readily accessible, and accommodating to the needs of all occupants;

- The Regulars: regular participants help set the mood and tone of a third place, attract newcomers, and help newcomers feel welcome and accommodated;

- Low Profile: third places feel simple and homey, without extravagance or pretense, and are accepting of individuals from all walks of life;

- Playful: the mood and nature of third places is playful, full of wit and banter, and generally free from tension and hostility;

- A Home Away from Home: in third places, occupants feel the same sense of belonging, warmth, connection, and protectiveness and possession that they feel in their own homes.

Third places unify communities without barriers, allow for networking and the sharing of resources, foster intergenerational relationships, provide free unstructured exploration, and promote social interchange and the exchange of ideas. Unfortunately, urban planning and capitalist interests have led to a decrease in an already-low presence of third places in the U.S (as compared to other countries around the world). Oldenburg argues that the decline of third places has contributed to the deterioration of community and civility and led to increased isolation and division within American society.

This is where the public library steps in to play a vital role.

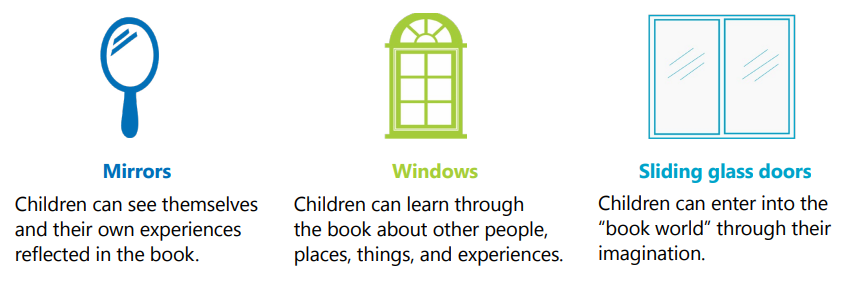

In our digital age, with the internet and e-books, audiobooks, online libraries, online databases, streaming services, and online shopping, the public library is no longer only (or the primary) place to access books and information. Now and on the horizon, public libraries need to meet not only the information and digital needs of patrons, but also serve as community hubs and social services, or “third places.” As the Covid-19 pandemic shutdown showed us, while technology will continue to make our lives more convenient and help connect us to each other, digital connectedness cannot make up for a lack of physical human connection, social interaction, and cultural exchange.

How Can Libraries Function as Third Places?

In his 2001 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Robert D. Putnam discusses two types of social capital: bonding, in which people with a similar sense of identity are brought together, and bridging, in which disparate groups of people are brought together in a common cause. Libraries can provide both bonding and bridging, by giving community members a place to meet with others like them (bonding) as well as by providing a space and programs and services to allow community members to come together in spite of (or because of) differences (bridging).

Libraries are one of the only truly free, accessible community spaces that remain in existence in the U.S. While libraries at their foundation fulfill the eight characteristics outlined above, Colorado’s Anythink Library is a stellar example of how libraries can foster these ideals to more richly function as third places. Anythink‘s whole philosophy is based on the idea that community members can do anything they can think of there, instructing patrons to “find delightful opportunities to learn about anything under the sun in the most beautiful, comfortable spaces. Our libraries are community assets that belong to you…The more imaginative and collaborative we can be, the better we can serve our customers” (Anythink Libraries, n.d., brochure).

I spent some time in Spain several years ago (*see images below), and I fell in love with the abundance of third places and how easy it was to find community there. Our infrastructure in the U.S. is so vastly different that it is difficult to create third places that so conveniently and easily meet the needs of our sprawled-out society. However, Anythink is doing just that. With seven branches plus outreach services, Anythink is bringing third places to the members of the Adams County community. An example of this is their Community Center Branch in Thornton, Colorado. Partnering with the city of Thornton, the library is housed within the Community Center and includes a reading fireplace, study rooms, teen space, children’s space, and a studio makerspace, in addition to recreational spaces such as a gym, dance studios, and boxing gyms, as well as shared spaces perfect for community events and gatherings (community center amenities are available for a very nominal fee, ranging from $2.00 – $5.75 daily for Thornton residents) (City of Thornton, n.d.).

I am also quite inspired by Anythink’s Nature Library that is under construction in Thornton. In a society such as ours, where being outdoors often means being alone (either on an isolated nature trail or in one’s own private backyard), the potential for a common outdoor space to become a third place for Thornton community members is promising.

While I have mostly focused on physical third places here, I don’t want to overlook the potential for online third places to also meet the needs of communities in today’s digital age. During the Covid-19 crisis, libraries helped fill the role of third-place when they moved services online to offer virtual homework help, storytimes, yoga classes, concerts, Zoom social hours, and more. In this way, the Internet has become a kind of a third place as digital communities have emerged to meet the needs of a growing digital society. There are so many possibilities for libraries to fulfill the needs of communities as third places, both physically and digitally. Wood states, “Whether onsite or online, libraries have proven their third-place designation” (Wood, n.d., para. 2).

My Reflection on the Future of Libraries as Third Places

Learning about the importance of third places, and how libraries can act as third places, will inform how I look at my work as a librarian moving forward. While I love books and reading, and that was definitely a driving force in my decision to pursue librarianship, my love for community and serving and connecting with my fellow humans is at the forefront of my passion for this work. I am committed to better meeting the needs of my community through library spaces, programs, and services to foster improved social connection, mental health, digital literacy, and accessibility. Historically, third places have often been the backbone of human rights movements (Oldenburg, 1997), and while the future remains uncertain, I have hope that libraries and librarians will continue to serve communities as third places through their constant committment to providing free access to information and services.

*Third Places in Europe

Clockwise from top left: a public “platz” in Salzburg, Austria allows for social gathering and impromptu encounters; an intergenerational game of “parchís” in a “plaza” in Alicante, Spain; a “piazza” in the pedestrian zone of Bologna, Italy welcomes families and friends to gather while walking and cycling and visit in groups on building steps, city walls, and chairs; children meet to play at a “plaza” in Alicante, Spain; a public art installation in a “plaza” in Madrid, Spain invites conversation and connection.

References

Anythink Libraries. (n.d.). Anythink brochure. Retrieved on November 20, 2024, from https://www.anythinklibraries.org/sites/default/files/imce_uploads/Anythink%20Brochure.pdf

Anythink Libraries. (2012, October 31). A day in the life of an Anythink Library [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/VLUFz5aGFQc?si=QRXqRrLeiIOKFeGU

City of Thornton. (n.d.). Thornton community center. City of Thornton: Parks & Recreation. Retrieved on November 20, 2024, from https://www.thorntonco.gov/parks-recreation/recreation-facilities/thornton-community-center

Gaetani, M. (2018, November 11). Q&A with Eric Klinenberg. Stanford University: Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. https://casbs.stanford.edu/news/qa-eric-klinenberg

Oldenburg, R. (1997). The great good place: Cafés, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons and other hangouts at the heart of a community (2nd ed.). Da Capo Press.

Putnam, R. D. (2001). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

Safdie Architects. (n.d.). Salt Lake City Public Library. [Photograph]. Retrieved on November 20, 2024, from https://www.safdiearchitects.com/projects/salt-lake-city-public-library

Wood, E. (n.d.). The rise of third place and open access amidst the pandemic. American Library Association: Intersections. Retrieved on November 19, 2024, from https://www.ala.org/advocacy/diversity/odlos-blog/rise-third-place