In INFO 204 Information Professions, which I took last semester, a large part of the curriculum was working as a group to come up with solutions to real-life management problems faced by public librarians. The one that stuck with me the most was about censorship. From my recollection, a librarian was faced with a patron who wanted to remove an art book that she believed had inappropriate material for children, and it was our job to think about the key issue in the scenario and suggest how the librarian should have handled the situation. While the solutions focused on policy and librarian training, I had a hard time coming to terms with the realization that book banning and censorship is a very real problem.

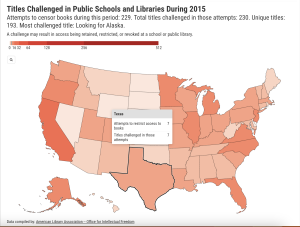

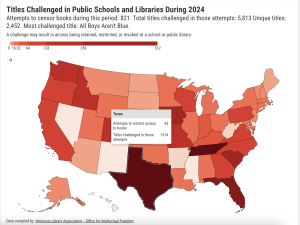

In fact, as I was reading through the materials in the hyperlinked environment section, I learned just how prevalent book banning efforts have become. According to the ALA’s Censorship by the Numbers tool, there were only seven attempts to restrict access to books in Texas (and seven books challenged in the attempts) in 2015, while in 2024, there were 43 attempts to ban a total of 1,514 books. This increase is astounding to wrap your head around. I had to sit and let those numbers sink in and think about why this is happening. The ALA points to a number of causes, including the pandemic leading parents to become more involved in their children’s education and the highly politicized world we currently live in, with organizations and people wanting to ban titles that don’t align with their religious, political, or moral beliefs.

During my training as a volunteer at the public library where I work, the head librarian who trained me spoke about censorship from another angle than book banning. She said as a librarian, it is your responsibility to help people find the information they are looking for. If someone approaches her and asks for a copy of Mein Kampf (which I believe is the example she used), she has to help them find it without judgement. This idea has stuck with me as I’ve been asked to reshelve books about Donald Trump and other topics I personally am not aligned with. Do I wish these books didn’t exist? Sure. But would it ever occur to me to try to ban them from the library? Never.

It makes me wonder what is the best way to get people who want to ban books understand why what they are doing is wrong. After all, if they want to read a book about Hitler, it doesn’t mean it will turn them into a dictator who will initiate genocide, in the same way a teenager reading a book with gay characters won’t “turn” them gay. However, according to the Washington Post article, reasoning with them about the subject matter doesn’t seem to be the right approach—though I did love the thoughtful and gently snarky letter that the author Bill Konigsberg wrote to Texas parents who wanted to ban his books.

It never occurred to me that library systems should fight book bans by avoiding arguments about the subject matter. “In a red state or town, that might mean public testimony shouldn’t emphasize that books by or about LGBTQ people or people of color are disproportionately challenged. It could backfire, explains Peter Bromberg, associate director of EveryLibrary,” writes Aylssa Rosenberg in the Washington Post. Instead, she says, libraries should focus on the costs of censorship and how it wastes public resources. I’ll be honest, this makes me incredibly frustrated that libraries have to try and fight censorship without actually arguing that it’s wrong, and instead pointing to things like cost and litigation risks.

I loved reading about the libraries that are fighting back, including the New York Public Library’s Freedom to Read project. Programs like NYPL’s Teen Banned Book Club and Teen Voices magazine are so critical right now because they teach teenagers (and maybe future information professionals and librarians!) about the current environment around book bans and empower them to speak up and take action. If I do end up in a library where the majority of my patrons are students, I would want to take the same approach.

One last thing in the module’s materials that resonated with me was something that the therapist interviewed in the video about Gender Queer said. It was about how telling people to just buy the books they want to read shows privilege and that libraries are about providing access to people who can’t go out and buy what they want. It made me think specifically about kids and teenagers who likely don’t even have their own credit cards and who think of the library as a place where they can explore thoughts and feelings they have without getting their parents’ permission. It’s how I used the library growing up, and it’s what I want for my children and community at large.

References

American Library Association. (n.d.). Censorship by the numbers. Banned Books. Retrieved June 20, 2025, from https://www.ala.org/bbooks/censorship-numbers

Konigsberg, B. (2022, March ?). An open letter to parents who wish to ban my books from school libraries. Retrieved June 20, 2025, from https://billkonigsberg.com/an-open-letter-to-parents-who-wish-to-ban-my-books-from-school-libraries/

Rosenberg, A. (2023, April 5). How to fight book bans — and win. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/04/05/book-bans-how-to-fight/

The New York Public Library. (n.d.). Books for all: Protect the freedom to read. Retrieved June 20, 2025, from https://www.nypl.org/spotlight/freedom-to-read