Author: Krista Holmquist (Page 1 of 2)

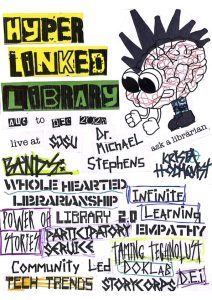

For my virtual symposium, I turned some of the key takeaways from the course into a DIY Punk style flyer. I think that the ethos of the Hyperlinked Library is pretty punk at its core, so I thought this was only fitting. I see the idea of the Hyperlinked Library as an alternative to the old, mainstream ways of library service. It’s inventive, ‘cutting edge’, and defies tradition. The Hyperlinked Library shows us that rejecting what’s no longer working is okay; that change is inevitable, and even good. The Hyperlinked Library is community, it’s active participation in meaningful change, it’s transformative, it’s counterculture– it’s punk!

I hope you enjoy my silly way of showing how much this class meant to me. I look forward to bringing these ideas into my career as a librarian, and am excited to be part of the transformative culture of the Hyperlinked Library.

As Stephens (2025) mentions in his Library as Classroom lecture, “libraries create and facilitate connections”. This is especially true when we think of the ways libraries have transformed their programming to fit the learning needs of their communities. In person and online learning opportunities have become the norm in libraries everywhere, as librarians step into roles as curators of the learning experience (Stephens, 2016). With community-driven course opportunities, libraries have stepped in to augment learning and have solidified themselves as part of the classroom experience. This is evident in the many educational programs in public libraries, as well as the development of online courses. The library has become a classroom and a place to learn from anywhere and everywhere.

When I think of the library as a classroom, my own experiences as a homeschooling parent come to mind. In the homeschool community, the library is an invaluable resource for enrichment, socializing, and supplementing education. In thinking of the future of teaching and learning, Lippincott (2015) discusses “active learning and learning as a social process” in terms of library collaboration with higher education institutes. This is something that particularly resonates with the homeschool community, as well. With a steadily growing homeschool population in the United States, libraries are well-positioned to provide active learning and teaching resources to homeschoolers, and many are already taking on this challenge.

At San Diego Public Library (SDPL) in California, they have developed a homeschool resource center to help home-based learners and their teaching parents. Johnsburg Public Library in Illinois has also developed a homeschool resource center. Both libraries provide curriculum materials and educational manipulatives available for check out, commonly needed office supplies and machines like laminators and copiers, as well as social and learning opportunities for homeschool families through clubs, classes, and more. The centers are designed as a large classroom, and are available to reserve for homeschool co-op meetings, programs, and more. These centers are open to anyone, not just homeschool families, but are designed to enrich the lives of home-based learners and educators. Johnsburg Library goes above and beyond, offering one-on-one meetings with the library’s educational consultant, provides information to local homeschool co-ops and groups, and breaks-down education and teaching philosophies for families. This high level of dedication to providing resources to library goers, and more specifically to homeschoolers, shows the depth of the ways libraries are adapting to the educational needs of their communities. With so many learning and social opportunities provided, libraries are an infinite learning resource for homeschoolers.

Recently, libraries have also ramped up their digital resources and online classes. This is useful to all library users, of course, but is yet another tool that really helps in home-based learning. Seattle Public Library (SPL) provides online access to a wealth of courses for all ages. From adult tutoring to online curriculum resources, SPL has taken the concept of library as a classroom to the next level! SDPL also hosts many online learning opportunities and has organized these resources by grade level and subject in the homeschool resource center section of their site, with Johnsburg Library also hosting a specific area of their site for online homeschool resources.

In the most literal sense, the library is what homeschoolers look to as their classroom. Homeschoolers are always in search of enrichment opportunities for their children that have the added benefit of socializing or a learning experience. The library is often used to achieve all these things wrapped into one. Libraries have come a long way in their work to serve their communities as educators, and the ways they benefit homeschoolers are virtually endless. Libraries and librarians are partners in teaching our communities and the possibilities in these endeavors are endless—they are wholly and truly “spaces of infinite learning” (Stephens, 2014).

References:

Lippincott, J. (2015). The future for teaching and learning. American Libraries. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2015/02/26/the-future-for-teaching-and-learning/

Stephens, M. (2014). YLibrary?: Making the case for the library as space for infinite learning.

Stephens, M. (2016). The heart of librarianship: Attentive, positive, and purposeful change. ALA Editions.

Stephens, M. (2025). Library as classroom. [Video] Panopto recording. https://sjsu-ischool.hosted.panopto.com/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=c716d09f-f8cf-4a08-bef8-af34011f855e

There is nothing quite as unique or powerful as our personal stories. These stories shape not only who we are, but the environment around us. When we step into professional roles, our unique personal stories follow us into these roles and shape the institutions we become a part of. When we hold space for these stories, powerful movements arise.

In library service, the value of personal stories shows itself in a variety of ways. Diverse staffs and communities shape the way these stories play out in library services. Through inclusive collections that tell the stories of the communities we represent, in planning programs and services that reflect this, and in a staff that mirrors the diversity of the community, libraries show how the power of stories moves us.

Perhaps one of the greatest tools in growing community is learning about those around us. Coming to know these stories through “The Human Library” project is a great example of the ways libraries invest in the power of stories. In this project, libraries create the opportunity for community growth and intentional exchange of ideas by curating a group of diverse individuals as “books” available for “rental” (Wentz, 2013). When “readers” check out their human “book” to learn their story and ask questions, magical things happen—acknowledgment and reflection of internalized biases, open and continued dialogue, and further growth of the human library project through the passion gained for sharing these experiences (Human Library, 2021). When we have the opportunity to learn the unique narratives of the people around us, we gain understanding; and with this understanding, we become empowered participants of our communities who are equipped with knowledge of the interconnectedness of our stories and more capable of empathizing with the people around us.

The Human Library shows us just one of the many creative and innovative ways libraries are shaping their communities through the power of stories. Libraries everywhere are ramping up their inclusivity practices by diversifying their collections to represent people of all kinds. This, of course, comes in the form of books but also in many other imaginative ways. Through oral histories projects, libraries everywhere are gathering collections of oral history from members of the community, giving people the ability to share their stories with the public. Los Angeles Public Library hosts a remote oral history platform called Their.Story, helping the community “collect, preserve, and engage with audiovisual stories of their members” (LAPL, n.d.). On the site, anyone can record their story of the impact libraries have had on their lives. Other oral history collections tell stories specific to important figures or groups of people, giving us the ability to see into the personal lives of others.

The Human Library shows us just one of the many creative and innovative ways libraries are shaping their communities through the power of stories. Libraries everywhere are ramping up their inclusivity practices by diversifying their collections to represent people of all kinds. This, of course, comes in the form of books but also in many other imaginative ways. Through oral histories projects, libraries everywhere are gathering collections of oral history from members of the community, giving people the ability to share their stories with the public. Los Angeles Public Library hosts a remote oral history platform called Their.Story, helping the community “collect, preserve, and engage with audiovisual stories of their members” (LAPL, n.d.). On the site, anyone can record their story of the impact libraries have had on their lives. Other oral history collections tell stories specific to important figures or groups of people, giving us the ability to see into the personal lives of others.

StoryWalks are another way libraries are incorporating inclusive narratives into their services. The Magnolia Neighborhood branch of Seattle Public Library has hosted a StoryWalk of Indigenous stories for five years. On an outdoor trail near the Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center, a story is arranged on sign posts for visitors to read along their walk. Thesestories, written by native authors, share the history and culture of Indigenous communities with the public through a fun and engaging participatory event.

By sharing our stories, listening to the stories of others, and collecting and cataloguing stories to be preserved and shared with the public, libraries are doing the important work of engaging the community in meaningful reflection and learning about the people around us. Strength is found in our communities when we share the power of stories.

References:

Arne-Skidmore, E. (2021, April 8). Human library impact study. The Human Library. https://humanlibrary.org/new-study-on-the-impact-of-the-human-library/

LAPL. (n.d.). Their.Story. Los Angeles Public Library. https://www.lapl.org/theirstory

Stephens, M. (2019). Wholehearted librarianship. ALA Editions.

Wentz, E. (2013, April 26). The human library: Sharing the community with itself. Public libraries online. https://publiclibrariesonline.org/2013/04/human_librar/

When discussing shifts in library service, it is important to mention the ways library outreach is transforming. Social media has long been part of library outreach, but in recent years, this has taken new form. With the rise of TikTok, libraries around the world have begun to participate in a refreshed, and even more trendy, social media landscape. As the IFLA Trend Report of 2024 explains, young adults prefer to use social media for receiving their news and other important information. This is something that, in recent years, libraries have caught onto and have begun to use to their advantage. Through short-form video content, libraries can create online engagement with their communities and even those outside of their communities.

This form of digital outreach has far surpassed the usefulness of its social media predecessors. TikTok has become a go-to space to receive information, and short-form video content is transforming the information landscape. With this transformation in the way we search for and receive information, libraries have found their niche. This social media tool has already proven its usefulness to library outreach and engagement, with many public libraries gaining follower counts in the tens and hundreds of thousands.

Creating cult-like followings through funny videos, or by using their content to inform about library services and programs, libraries and librarians are using TikTok to grow support and engagement. Librarians like Mychal Threets (@mychal3ts on TikTok) have become viral sensations, gaining large followings and, thus, the ability to bring awareness to library services and issues related to libraries to their audience. Furthermore, TikTok users have popularized their local libraries by visiting, creating videos, and adding to the #library tags.

The potential for outreach growth through this social media app is tremendous and will continue to be seen for years to come. This, then, posits the question of how libraries may continue to see success through TikTok outreach methods and the future incorporation of short-form digital media in libraries and the information landscape. It is not far-fetched to imagine that libraries may begin to hire content creators and managers for their TikTok accounts, to keep up with this growing asset. Just as there are outreach teams, it is likely we will see a transformation in this area and the rise of social media specialists and content creation teams for libraries.

In recognizing the transformative stage of the information landscape we are in, libraries are participating in social media trends and revamping interest and community participation, while exposing new audiences to library advocacy efforts. Growing an online following has become a crucial step in the success of many businesses, and libraries, too, have bought into this business plan. In doing so, a new generation of library goers is growing via the virtual community of TikTok.

“I can say without hesitation that our library program would not be as successful, supported or engaging were it not for our robust social media presence. To serve our students, we need to speak their language and we need to live where they live. And right now, a lot of our students are speaking and living TikTok. And so should we.”- Kelsey Bogan, 2020

References:

Bogan, K. (2020). TikTok and libraries: A powerful partnership. Schools catalogue information service, 115(4). https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-115/tiktok-and-libraries-a-powerful-partnership/

Dezuanni, M., Osman, K., Burton, A., & Heck, E. (2024). IFLA trend report 2024: Facing the future of information with confidence. https://repository.ifla.org/handle/20.500.14598/3496

Public libraries are adapting to the growing and changing needs of modern library users by reimagining the library environment. The library is no longer simply a place to borrow books; it is a community hub where people come to engage in creative pursuits, socialize, and collaborate. Innovative design and collection materials have become cornerstones of the efforts to modernize and redesign library spaces. Cultivating an environment of community, public libraries have officially “rebranded” (Grant, 2021).

The public library has become an extension of the community it serves, and a place for “community vitalization” (Skot-Hansen et al, 2013). The programs, services, materials, collections, and overall design of the library building have changed to appeal to a sense of community consciousness, creativity, and entrepreneurial skills. In examples like The Hive in Spokane, Washington  or Cloud901 in Memphis, Tennessee,

or Cloud901 in Memphis, Tennessee,  we see wholly reimagined spaces that are dedicated entirely to developing skillsets and artistry through access to the necessary (and often inaccessible) facilities and devices. Here, we see music and photography studios, art and event spaces, sewing rooms, and much more. Makerspaces like these are cropping up in public libraries all around the world, showcasing the innovative modern library environment and its dedication to cultural and community revitalization through creativity, collaboration, and connection.

we see wholly reimagined spaces that are dedicated entirely to developing skillsets and artistry through access to the necessary (and often inaccessible) facilities and devices. Here, we see music and photography studios, art and event spaces, sewing rooms, and much more. Makerspaces like these are cropping up in public libraries all around the world, showcasing the innovative modern library environment and its dedication to cultural and community revitalization through creativity, collaboration, and connection.

When thinking of a hyperlinked library, spaces like these are exactly what come to mind. These spaces are fun and engaging for every age– they’re somewhere you want to come hang out, not just go to borrow books. Public libraries have taken the initiative to discover what their community wants and needs and have risen to the occasion in providing access to the necessary materials and equipment to fulfill these. Through the development of Library of Things in many public libraries, we further see this environmental shift away from solely books and into a broader and more fulfilling access initiative that works to serve the needs of the community.

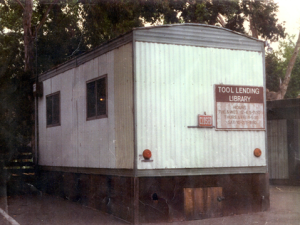

Today’s Tool Lending Library in Berkeley, CA

The Tool Lending Library in Berkeley, CA in 2012

It is evident, then, that public libraries have come into a new role. No longer simply buildings filled with books—the public library has been completely reinvented to a meeting space and one of the last remaining, true third spaces of the modern world. While third spaces deteriorate and disappear throughout the U.S., we see libraries stepping into this role by revamping their spaces, programs, services, and materials. From “hushed book repository” to a fun, imaginative space to create, learn, and network—libraries have successfully completed the ultimate rebrand; and have become an environment where community can flourish and grow (Grant, 2021). It is amazing to think of how far public libraries have come, just in the last couple of decades alone!

“The real power of libraries is they can transform people’s lives. But libraries can also be fun”

-Keenon McCloy (Grant, 2021).

References:

Grant, R. (2021). How Memphis created the nation’s most innovative public library. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/memphis-created-nations-innovative-public-library-180978844/

Skot-Hansen, D., Hvenegaard Rasmussen, C., & Jochumsen, H. (2013). The role of public libraries in culture-led urban regeneration. New Library World, 114(1/2), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074801311291929

Hyperlinked communities are an especially important part of library discourse, as it is libraries who help lead our communities by providing access to knowledge, resources, and safe spaces to build and grow diversity. As the United States faces an administration that is, seemingly, determined to undermine facts and to eradicate all efforts of diversity equity, and inclusion in our systems, it is more important than ever for libraries to take initiative and lead the way in building strong communities that advocate for its users, while providing equitable service and access. As Garcia-Febo (2018) explains, we need to be “creating institutions that expand minds and open futures” through love, empathy, and open hearts.

At a time when American institutions are repealing rights from marginalized groups, libraries stand as a beacon of hope to our communities. As Jensen (2017) explains, “It’s impossible to be a neutral space with the goal of reaching a community”. The inherent nature of libraries is political—to educate, to stand up to injustice, to fight misinformation, and to provide free resources to the underserved. By providing equal access and equitable services to our communities, libraries provide a space to educate people from diverse backgrounds; to include and represent everyone. While the Trump administration takes away federal funding, removes DEI terminology from professional vocabulary, and censors and bans the books and information allowed in library spaces, librarians still fight back.

Founded by Brooklyn Public Library, a network of libraries across the U.S. have come together to create Books Unbanned; a system inspired by the ALA’s Freedom to Read Statement and Library Bill of Rights, made to combat book bans across the U.S. (Books Unbanned, n.d.). Books Unbanned gives free digital library cards to teens and young adults, in the effort to give access to banned books in places where censorship and book banning laws have gone into effect. This equitable access initiative is a prime example of building a hyperlinked community. By using modern technology, namely e-book collections, libraries are fighting to keep all books accessible to all people.

It is important for libraries to acknowledge all forms of access barriers and how to address these through services and community building. As we face increasing efforts to undermine education and diverse sources of information, it is more important now than ever for libraries to stand together in uplifting our communities through access initiatives, and diverse and inclusive materials. I resonate deeply with the ideas mentioned by Garcia-Febo (2018) and Stephens (2016) in leading and learning from the heart with our work as library and information professionals. This notion will lead us far in our work and the ongoing fight for intersectionality, diversity, equity, and inclusion in libraries. When libraries strive to create spaces that include diverse materials with representations of all people, we are successful in creating hyperlinked communities.

References:

Garcia-Febo, L. (2018, November 1). Serving with love: Embedding equality, diversity, and inclusion in all that we do. American Libraries Magazine. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2018/11/01/serving-with-love/

Jensen, K. (2017, February 10). Libraries resist: A round-up of tolerance, social justice, & resistance in US libraries. Book Riot. https://bookriot.com/libraries-resist-round-tolerance-social-justice-resistance-us-libraries/

Stephens, M. (2016). The heart of librarianship: Attentive, positive, and purposeful change. ALA Editions.

The concept of participatory service in libraries stands out as one of the foremost ways modern libraries engage in growing their communities. More than just a book repository, libraries have become community hubs—places for engaging in and sharing creativity. Participatory service is more than library social media accounts or measured survey input, it is a dedication to growing and sustaining community engagement through interactive connection. As Casey (2011) explains, “The participatory library engages and queries its entire community and seeks to integrate them into the structure of change”. While public input is the catalyst for participatory service, it is only the beginning of a multifaceted system which aims to create a library culture of active involvement and community planning and commitment. As Casey & Savastunik (2007) describe in Library 2.0, the idea of a top-down service model has become obsolete; forcing libraries to evolve the way they structure their resources, and, ultimately, leading to the evolution of the participatory service model (p. 61). The importance of surveys, comment cards, and online input from patrons should not be understated—for it is this input which drives the development of participatory services within the physical library space. With this community input, libraries around the world can create programs, services, and daily interactions that increase participation in their physical library spaces; empowering library management to develop meaningful, quality services that fit the needs of their communities.

As libraries have evolved, the resources available have become increasingly focused on developing a framework of active participation within the physical space of the library. Through interactive display features within the library, users can have daily engagement with varied forms of participatory culture.

DOK Library, Netherlands.

This can be seen in libraries like DOK in the Netherlands, where a large touchscreen Surface table is used to display Flickr photographs from the library account, allowing patrons to interact with the device by browsing and downloading displayed photos of library users (Stephens, 2011). DOK library also uses this Surface table in their interactive Heritage Browser, a tool that implements collaboration through photographic story sharing (Boekesteijn, 2011). These tools blends the online and physical community spaces of the library, allowing users to lend their photos, stories, and other ideas to this digital space to be accessed by other library users to exchange information through the Surface table interface. This blending of online and physical communing is a brilliant way to showcase libraries’ evolution of innovation in participatory service models.

To take this idea of daily accessible forms of interactivity further, it is important to mention library makerspaces. These spaces are dedicated to fostering creativity and community, on-site, through their available resources. This is evidenced in spaces like YOUmedia at Chicago Public Library (Chicago Public Library, 2016) and the James B. Hunt, Jr. Library at NC State University (NC State, 2013). Through these supremely interactive spaces, library goers are encouraged to fully immerse themselves in the library space and its community. NC State describes their library space through experience,

OctaviaLab, LAPL

innovation, creation, collaboration, immersion, and education (NC State, 2013), encapsulating the true form of the participatory service model. LAPL houses the OctaviaLab, a maker space chalked full of creative tools and equipment, with a variety of learning opportunities available to users. These makerspaces are used as a means for community meeting and sharing. In these spaces, peer interaction and learning naturally lends itself to community development. By engaging in makerspaces and the programs and services they offer, community growth and participatory culture is fostered and encouraged through direct communication, learning, and creating with likeminded peers, as well as library staff. Extending these tools for makers outside of the library walls, library of things and tool lending libraries provide further participatory service to patrons. With these service forms, libraries once again blend their engagement from within and outside of the library’s physical space.

Using community input to guide participatory service has led libraries to services that engage their communities online, at the library, and at home. No longer simply a place for books, libraries have become community hubs for creativity and peer-to-peer learning and networking. Libraries have transformed into places of interactive communication, where experience-oriented learning leads the way in participatory service and library culture (Rasmussen, 2016). Holding these concepts in high esteem, it is my professional goal to continue the work in implementing this model of open, creative participatory discourse and service– to ensure libraries remain centers of culture, creativity, and learning in our communities for many years to come.

References:

Boekesteijn, E. (2011, February 15). DOK Delft takes user generated content to the next level. Tame the Web. https://tametheweb.com/2011/02/15/dok-delft-takes-user-generated-content-to-the-next-level-a-ttw-guest-post-by-erik-boekesteijn/

Casey, M.E., & Savastinuk, L.C. (2007). Library 2.0: A Guide to Participatory Library Service. Information Today.

Chicago Public Library. (2018, April 11). YOUmedia at CPL. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v8G4nnlgKmk

NC State. (2013, April 3). NC state university’s James B. Hunt, Jr. library. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=scyQPk6n0xA

Rasmussen, C.H. (2016, October). The participatory public library: the Nordic experience. New Library World. 117 (9-10) 546–556. https://doi.org/10.1108/NLW-04-2016-0031

Stephens, M. (2011, November 7). Erik Demonstrates Surface & Flickr App. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OCpY5zTv2Xo

August 23, 2025:

I am currently reading The Hobbit by J.R.R Tolkien aloud with my 6 year old son. We have just reached the Desolation of Smaug, and are nearly finished with the book. I am thoroughly enjoying watching him experience Tolkien for the first time, and am so happy to see how much he’s interested in it!

August 23, 2025:

In my own reading, I am currently finishing up Slewfoot; a dark-fantasy novel about a witch and her demon companion, set in a Puritan colony in 1666 New England. I don’t usually enjoy fantasy novels this much, but I absolutely LOVE Slewfoot!

UPDATE: I finished Slewfoot, and I was obsessed. Such a good blend of fantasy and horror. I loved it so much. If you’ve read it, I must know!

September 2, 2025:

I just started East of Eden by John Steinbeck. Surprisingly, I’ve never read it before– so, I’m very excited to see what it’s all about. It’s been quite a while since I’ve read any literary classics. Does anyone have any juicy opinions?

What are you currently reading?