Introduction: The Library is Everyone

As access to digital technology and information continues to grow, the library is increasingly more than just a building, a collection, or an institution–it is a community. Indeed, as Michael Stephens’ hyperlinked library model asserts, “the library is everywhere,” (2016, p. 2), and with participatory services and community-based practices, the library can be everyone, too. With information and means of communication readily available to nearly all users in some form or another, librarians no longer need to be the guardians of knowledge, but can instead serve as helpful guides and leaders in their information communities. As the librarian’s role is being reshaped, so too is that of the library user. With the rise of participatory library services, users now have the power to contribute to their libraries in meaningful and impactful ways.

Citizen Science and Crowdsourcing

Outside of the library, collaborative online community projects have proliferated in the era of digital knowledge-sharing. One popular form this has taken is in “citizen science,” a term that can be broadly defined as scientific research which involves public participation or contribution (Haklay et al., 2021, p. 14). The concept has seen steadily growing interest in recent years and has been successfully applied in countless research efforts. One highly publicized example is Foldit, a puzzle game developed by researchers at the University of Washington, in which users contribute to protein folding research. Similarly, EyeWire, created by Princeton University researchers, is an open online game which uses user input to help map brain structure. Folidt and EyeWire use the power of crowdsourcing and gamification to advance complex scientific research.

But crowdsourcing is not only a popular and effective method in the hard sciences, and has in fact become a major part of online information sharing. Collaborative projects like Wikipedia (and other specialized “wikis”) have changed the landscape of knowledge sharing, and have resulted in a collection of information so broad and rich that it could only be achieved through wide, collective effort. Google Maps allows users to share photos of viewpoints and businesses, creating a collaborative mapping environment, while Archive.org takes a participatory approach to the preservation of media and webpages.

I have personal experience with a few crowdsourcing projects which I feel are excellent, community-based platforms. One of my favourites is LibriVox, a site that hosts audiobooks of public domain works, which are narrated by volunteer readers. Discogs is a popular site which functions as a marketplace for new and used vinyl, CDs, and cassettes, but has become the de facto source for information on release data for these media. Users have created a thorough database which details the release history of recordings, including production data and photos. iNaturalist is a great platform I was recently introduced t0, which allows users to upload photos of flora and fauna they come across, along with a corresponding geographic location. This data can then used by other users to help them identify local plants and wildlife, and helps scientists track species migration and biodiversity. Finally, I can’t possibly omit RinkWatch from this list, a site which tracks the location and skating conditions or public and private skating rinks through user contribution. The project has a twofold mission of documenting rink conditions for would-be skaters, and providing a store of data for climate scientists.

While these projects have vastly differing intent, scope, and scale, all can achieve what they do only through the immense impact of collaboration. Contributors are empowered to provide their time, knowledge, expertise, and experience to these projects, which provide for them a meaningful platform for engaging in a collective effort, and enable their participation in a community tied directly to their work. Users gain the benefit of expansive collections of knowledge and data, unmatchable in reach and breadth by most traditional means of publishing or data collection. The strength of these projects depend upon the agency of their community members.

Participatory Services in Libraries

The methods and principles underlying citizen science are echoed in models of participatory library services, and in programs being offered in libraries and information institutions today. Like citizen science and collaborative web projects, library users are harnessing expanded influence and through participatory service, creating a stronger library community.

The centrality and influence of the user is a core tenet of Casey and Savastinuk’s Library 2.0 model (2007), which “empowers library users through participatory, user-driven services” and thereby improves the user experience and expands the usership (p. 5). They describe users’ involvement in the “creation and evaluation of programs and services” as a path forward for progressive libraries (p. 14). Library 2.0 envisioned an institution which puts the user before the building or the collection. K. G. Schneider’s “The User Is Not Broken” (2006) offers a similar rebuke of traditional library thinking and hierarchies, declaring “the OPAC is not the sun…the user is the sun.” The user is not only our primary focus, they are our vitality. The same focus on the significance of the user is fundamental to Michael Stephens’ work with the “hyperlinked library,” which calls for the subversion of traditional organizational structures, advocates for team-based approaches (2016, p. 2), and asserts “the user is the center of this expanding universe of access and information” (p. 37).

Libraries today have embraced participatory practices, strengthening their connection to their users and successfully blending the library and the community. San Francisco Public Library is a great example, where librarians converted underused staff space to a cooperative teen zone. Librarians work with citizen groups and local partners to develop programming, consult the community on library decisions, and foster grassroots events and clubs through their “community rooms” (O’Brien, 2019). In the Netherlands, librarians at DOK Delft have created an interactive, touch display table, allowing users to upload photos, share stories and comments, and engage in debate and discussion, creating a model for the “library as a community storyhouse” (Boekesteijn, 2011). University of Iowa Libraries (n.d.) have created the DIY History project, which uses crowdsourcing to create a community transcription team for their digital collections. The result is a library which is both by and for the community, using the framework of citizen science to engage both local and global contributors. Similarly, the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (n.d.) has established “citizen archivist missions” which enlists users to tag and transcribe historical documents. These libraries are embracing the power of their users to create a stronger, more engaged community, and giving users the power to be a part of the library in new and profound ways.

Libraries and Users: Redefining the Relationship

The natural result of participatory, user-driven library services is that the traditional power dynamic between the library and the user has been subverted. The library is no longer the bastion of books, the stronghold of serials, the purveyor of programming–the library is a community, a collective space and knowledge.

At least, it can be (and should be). Traditional roles and structures persist, and change can take time. But many libraries and services are trending towards greater user involvement, and this transformation is taking many different forms. The move to participatory services is ongoing.

It is important to acknowledge that user participation is not a binary, a yes or no, or a box which can be checked. User influence is not created equal. A user comment box is not equivalent to a community-led oral history project. Both are participatory, but participation can be measured by degrees.

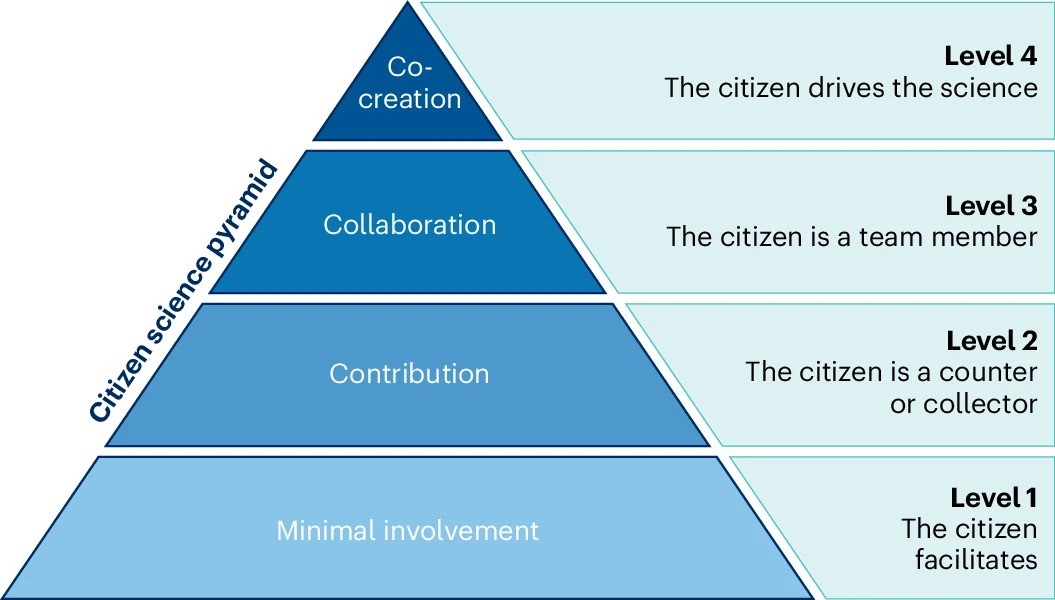

The “citizen science pyramid” pictured here provides a visual model for the range of user participation in citizen science projects, from a low-level, indirect involvement, to the zenith of co-creation and user-led output (Ahannach et al., 2024, p. 3447). The distinctions made here in the degress of user influence are helpful in considering participatory library services. Librarians can assess how their traditional, non-participatory programs may begin to involve users, while services which are already user-driven can be reviewed to determine how they can be more participatory. How can we move up the pyramid, from user involvement to co-creation? For libraries to maximize their impact, we must aim to climb the pyramid–to give users the agency to shape the library, and to create a library by and for the community.

By putting users first, and making them central to the library experience and community, libraries have begun to redefine the relationship between library and user. In fact, user is increasingly a misnomer, an inadequate descriptor for communities who not only use the library, but actively contribute, shape, and change it for the better. In participatory libraries, the people of our library community would more aptly be referred to as colleagues, allies, and partners–we work together, share common goals, and support each other.

References

Ahannach, S., Van Hoyweghen, I., Verhoeven, V., & Lebeer, S. (2024). Citizen science as an instrument for women’s health research. Nature Medicine 30(12), 3445–3454. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03371-2

Boekesteijn, E. (2011, February 15). DOK Delft takes user generated content to the next level – A TTW guest post by Erik Boekesteijn. Tame the Web. https://tametheweb.com/2011/02/15/dok-delft-takes-user-generated-content-to-the-next-level-a-ttw-guest-post-by-erik-boekesteijn/

Casey, M. & Savastinuk, L. (2007). Library 2.0: A guide to participatory library service. Information Today, Inc.

Gillis, D. (2018). Teamwork makes the dream work [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/KdeqA3aTnBY

Haklay, M., Dörler, D., Heigl, F., Manzoni, M., Hecker, S., & Vohland, K. (2021). What is citizen science? The challenges of definition. In Vohland, K., Land-Zandstra, A., Ceccaroni, L., Lemmens, R., Perelló, J., Ponti, M., Samson, R., & Wagenknecht, K. The science of citizen science (pp. 13-33). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58278-4_2

O’Brien, C. (2019). How San Francisco’s public libraries are embracing their changing role. Shareable. https://www.shareable.net/how-san-francisco-public-libraries-are-embracing-their-changing-role/

Schneider, K. G. (2006, June 3). The user is not broken. Free Range Librarian. https://freerangelibrarian.com/2006/06/03/the-user-is-not-broken-a-meme-masquerading-as-a-manifesto/

Stephens, M. (2016). The heart of librarianship: Attentive, positive, and purposeful change. ALA Editions.

University of Iowa Libraries. (n.d.). DIY History. https://diyhistory.lib.uiowa.edu/about-the-project

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). Citizen Archivist Missions. https://www.archives.gov/citizen-archivist/missions