Here’s the audio of my reflection (6:45) and also a transcript, if that’s helpful.

Here’s the audio of my reflection (6:45) and also a transcript, if that’s helpful.

A fun, if impossible, challenge is to imagine how technology will ultimately affect how people interact with information. Douglas Adams famously said that trying to predict the future is a mug’s game, but whether our exact predictions come to pass is not so important as having made them. Drawing a horizon gives us a sense of agency. It allows us to engage in planning even when we know the plans will change by the time we get there.

The NMC Horizon Report (2017) successfully predicted the rise of AI basically on the dot. Their projection was in four to five years and ChatGPT was release in 2022. They also previously listed machine learning, which is what AI currently is without so much gloss. Their observation that, “short term trends often do not have an abundance of concrete evidence pointing to their effectiveness” certainly resonates here at the end of 2025 as the AI bubble is predicted to pop.

The advent of AI for higher education is billed as a way to patch the problems introduced by increasing scale. Remote learning allows schools to admit more students but at the cost of individualized student experience. Learning mangement systems like Blackboard and Canvas are more efficient, but instructors can’t possibly respond meaningfully to an order of magnitude more students. The assembly line experience renders the education more alienating, though perhaps this is inevitable given the nature of online education as less embodied.

Either way, the prospect of AI in education is more individualized attention and reducing the effective student-teacher ratio. (The actual ratio may, paradoxically, increase if fewer instructors are now required for even greater numbers of students.)

A new technological affordance comes with two questions for librarians and teachers: (1) the general problem everyone faces about how to apply technology to generate value in their field and (2) the additional question of how to teach patrons and students the digital literacy they need to live in a world where that technology now exists. This is true even if they choose not to use it (EDUCAUSE, 2025) on ethical or practical grounds.

In teaching digital literacy around AI, the inability to scale LLMs may actually be a pedagogical feature not a limitation. Desktop or mobile hardware must run simpler models but this allows the experimenter to identify failure cases more easily. Thus students may ultimately better understand the importance of human-in-the-loop and the risk-benefit of using AI if they can more easily see it fail. This makes smaller models arguably better candidates for a learning lab environment. Running the models locally in the library also has privacy benefits for patrons since chats are not shared with technology companies rapacious for data.

References

Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M, Davis, A., Freeman, A., Giesinger Hall, C., Ananthanarayanan, V., Langley, K., & Wolfson, N. (2017). NMC Horizon Report: 2017 Library Edition. The New Media Consortium.

Robert, J., Muscanell, N., McCormack, M., Pelletier, K., Arnold, K., Arbino, N., Young, K., & Reeves, J. (2025). 2025 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: Teaching and learning edition. EDUCAUSE.

Image Credits

“img_7818” by Michael Hicks, CC BY 2.0

Arvo, J., & Kirk, D. (1987). Fast ray tracing by ray classification. ACM Siggraph Computer Graphics, 21(4), 55-64.

Most users don’t care about sources much of the time; they reach for whatever is at hand. Like Google, Wikipedia, friends and family, maybe a chatbot. Librarians care about the source a lot. We want to show why the source matters and provide access to those sources which provide the best, most relevant information. Users care more about the topic though, the information, the surprise, the finding out.

That’s why I was surprised to learn that first-year students at OSU working on their first research paper often skipped selecting a topic entirely (Deltering & Rempel, 2017). Instead, they chose a topic they already knew well. The decision is a strategic one: with their grade on the line and limited time, the risk in choosing the wrong topic is high. Between their perceived capacity and existing cognitive model of the subject, they choose the topic which minimizes research anxiety, but wind up with a topic for which their curiosity is actually lower.

This aligns with findings that 84% of students say getting started is the hardest part of research (PIL, n.d.). The easiest search is the one you already know how to do, but this reduces their motivation to explore new search strategies, thwarting efforts at information literacy instruction.

The challenge then is to create an environment in which users feel safe enough to explore a topic they are curious about but know very little. What is needed is a way to browse a wider range of high interest topics but with low stakes. The topics must be grounded in existing scholarly discourse so students have something to find. For this, OSU used press releases and news stories from sites like ScienceDaily. They also emphasized framing the exercise as exploring a topic over finding sources per se (Deltering & Rempel, 2017).

This helps students get a sense of what the literature might contain before they formulate a query. This is the paradox of search: you need to know what the index contains and how it is structured before you can effectively query it. Like many complex tasks, you learn along the way what you needed to know at the beginning.

There is a parallel in Matthews essay (2017) on how the organizational structure of academic libraries affects their ability to respond to change. The core argument is that libraries miss important opportunities because they are run too much like factories. If staff had more autonomy and fewer silos, they could better adapt and seize these opportunities.

Though it is hard to quantify, the opportunity cost is potentially quite large. The sense is that new tech-enabled modes of collaboration are such powerful multipliers that a nascent, globally distributed, cross-functional team is out there just waiting to invent the iPod or Taurus sedan of library services. (Are they hiring?)

The problem is the design space is simply enormous. In other words, academic libraries have a similar problem as students doing research; we don’t know what we don’t know, we don’t know which processes are repeatable. The best we can do is experimentation. Perhaps the solution here is similar: a way to explore a wider range of topics but with lower stakes, like allowing staff the (company) time to experiment. This way they can take risks, like first-year students, with less anxiety. Both would benefit from better ways to reward this exploratory research.

Deitering, A. & Rempel, H. G. (2017, February 27). Sparking curiosity: Librarians’ role in encouraging exploration. In the Library with the Lead Pipe…. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2017/sparking-curiosity/

Mathews, B. (2017). Cultivating complexity: How I stopped driving the innovation train and started planting seeds in the community garden. http://hdl.handle.net/10919/78886

Project Information Literacy (PIL) (n.d.), A National Study About College Students Research Habits [Infographic], Project Information Literacy Research Institute, https://projectinfolit.org/publications/retrospective#infographics

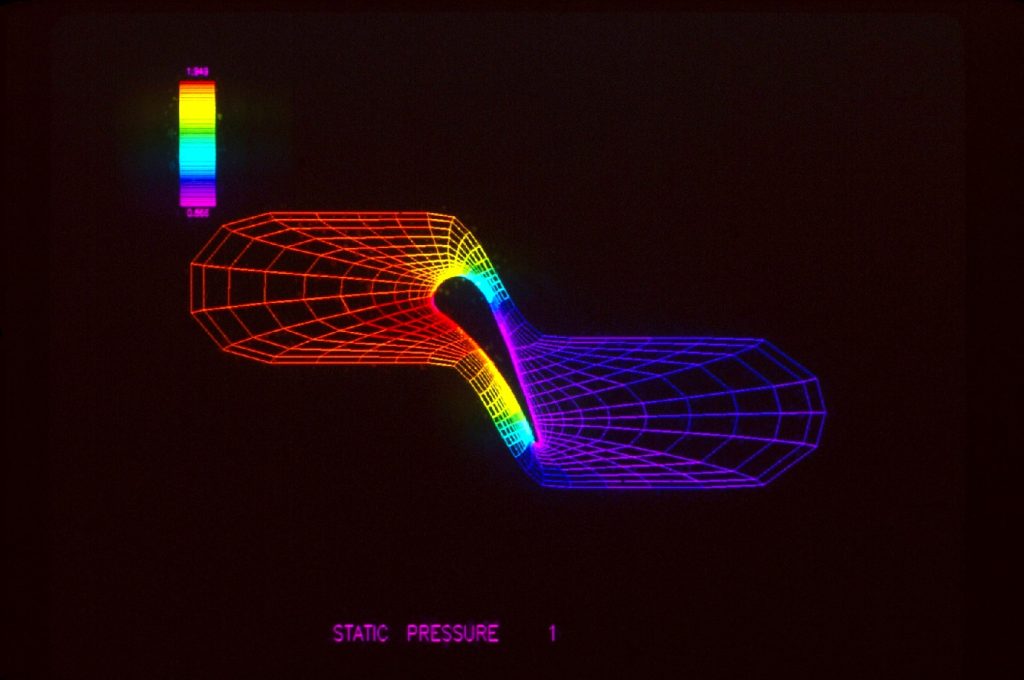

NASA. 1980s Visualization [image].

NASA. GRAPH3D [image].

Koppitch, A., & Schilling, H. W. (2025, July 23). GVIS lab at NASA Glenn research center history. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/centers-and-facilities/glenn/gvis-history-glenn/