Participatory service is an essential part of the hyperlinked library. With new possibilities for engaging with library users, we can better include them in both the development of new services and in the structure of the services themselves. That is, participatory service can be understood in two ways: (1) users participate in the design process and (2) the services themselves are designed to be participatory. (In principle, it is possible to have one without the other, but designing services to be participatory without somehow involving users seems ill-fated.)

Examples of soliciting user feedback abound: advisory groups, suggestions boxes, patron surveys, asking on social media, informal feedback during service interactions. These are rich sources of information about user needs and the kinds of services they might use. We can also bring users in as stakeholders to the service creation process through participatory design. The difficulty here is users do not always know what they want. “We can’t solve the mystery of the future of libraries by asking users what they want: they simply don’t know!” (Denning, 2015).

It is, of course, not their job to know; it’s ours. The common design adage is that users are poor designers but excellent refiners. Naively asking users to design new services is often inadequate given the complexity of the problem we are trying to solve. Their input is probably more helpful when reviewing an existing service or a new proposal. Inviting them to participate in the design process however is still enormously helpful! It provides insight into their holistic needs and mental models. Our challenge is to meet the needs which they, and we, have not thought of yet.

(Of course, sometimes we can just implement user suggestions. If they ask for an extra stapler near the printer, just put another stapler there.)

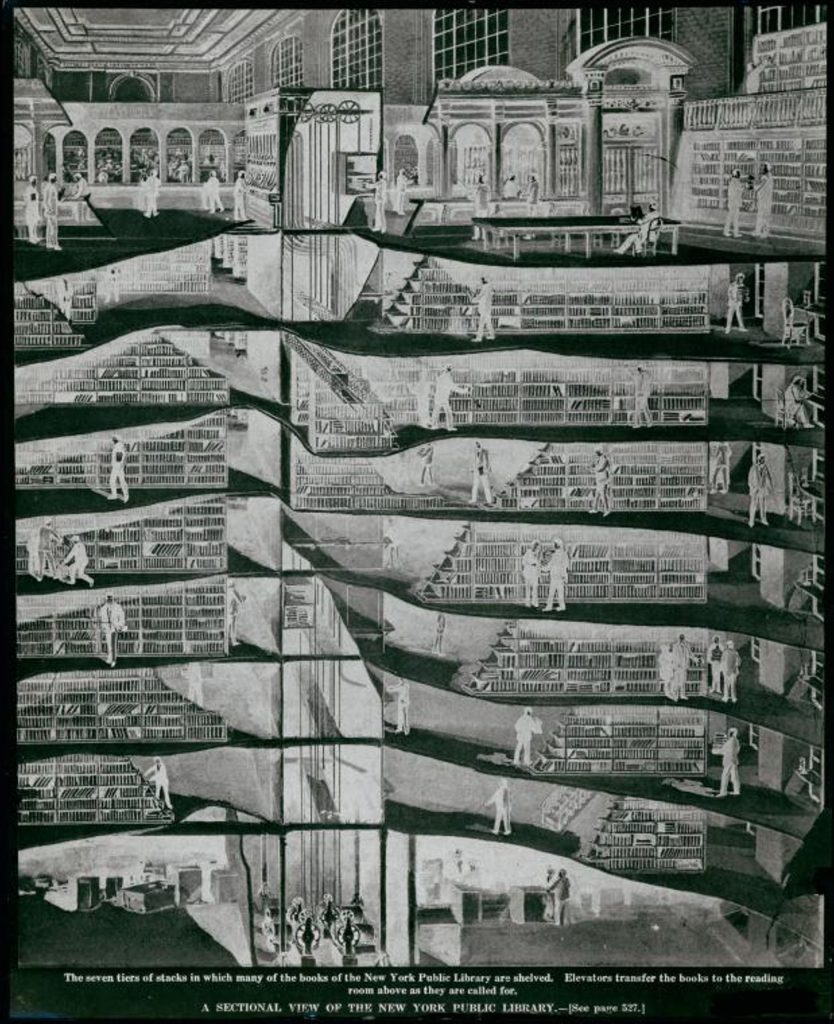

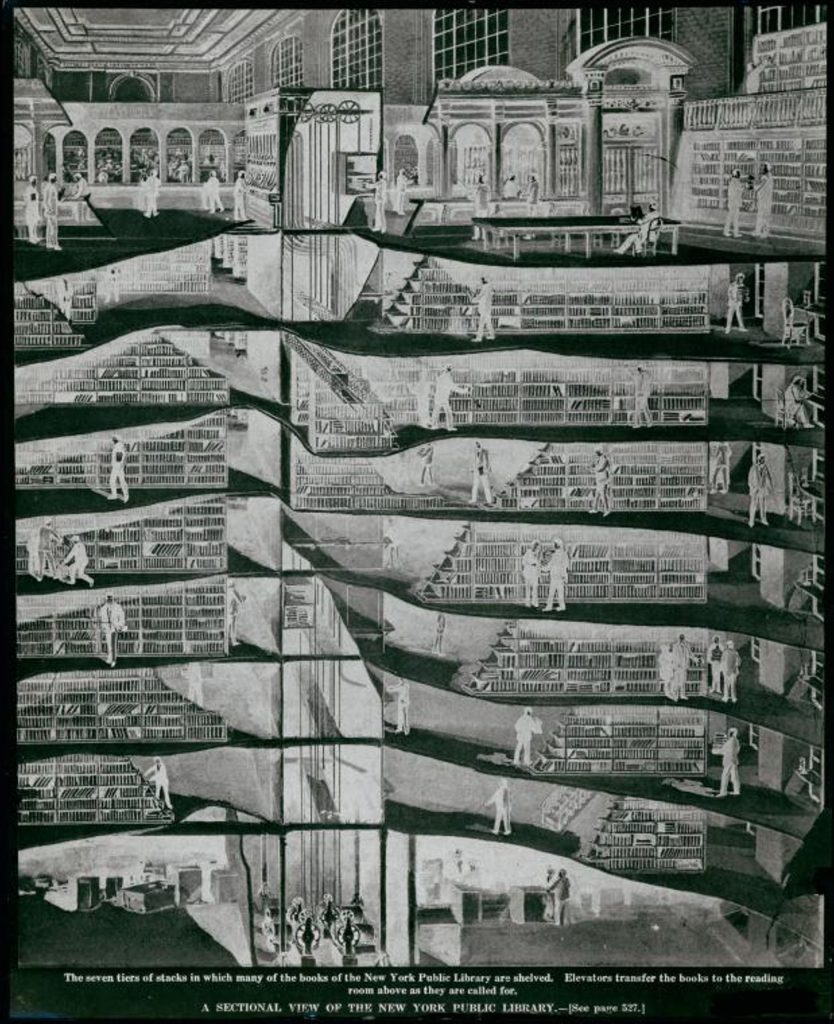

Participatory service is more than user input, however. The second sense is in the design of the services themselves. Information flows many ways now, and patrons want to tell their own stories. So, at DOK Delft, patrons can add, tag, and describe their own photos on a touchscreen table (Boekesteijn, 2011). Another example is patron-driven acquisition. “Letting the public have a role in ordering materials is one way to open a library’s collection to its readers” (Kenney, 2014). The US National Archives provides web users the opportunity to participate in collection processing by transcribing historical records and manuscripts (2025). In each of these cases, user participation is at the core of the design.

Beyond these two meanings of participatory library services, Michael Casey (2011) suggests a possible third. Quoting Tim O’Reilly:

“How do we get beyond the idea that participation means ‘public input’…and over to the idea that it means government building frameworks that enable people to build new services of their own?”

This understanding of participatory service might be expressed yet another way: (3) users can design services for themselves and one another.

This adds another level of abstraction. We can solicit user input on our participatory services, but we can also build platforms for users to create their own applications. Customizing and personalizing user interfaces is one example. Another is providing and documenting application programming interfaces (APIs) for digital collections and catalogs. This would require their knowing how to code however, excluding many users. We might imagine interfaces where users could mash-up library collections with other data sources. There was a trend during the mid-2000s for just this kind of application, e.g., Yahoo Pipes.

Note, however, that the complexity of the design challenge grows. This is not like making a web form or a multiplayer game; this is more like creating a game engine for users to make their own games.

I made a video game once. It was the hardest thing I’d ever done. I thought then that game design was the ultimate design challenge. I’m not sure now that libraries don’t actually hold this title. The prospect is daunting: designing the basic building blocks for users to create their own participatory information experiences. Nonetheless, this third kind of participatory service may help us fully realize the hyperlinked library as we move from user input to user participation and finally to user empowerment.

References

Boekesteijn, E. (2011). DOK Delft takes user generated content to the next level. Tame the Web. http://tametheweb.com/2011/02/15/dok-delft-takes-user-generated-content-to-the-next-level-a-ttw-guest-post-by-erik-boekesteijn/

Casey, M. (2011). Revisiting participatory service in trying times. Tame the Web. http://tametheweb.com/2011/10/20/revisiting-participatory-service-in-trying-times-a-ttw-guest-post-by-michael-casey/

Denning, S. (2015, April 28). Do we need libraries? Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2015/04/28/do-we-need-libraries/

Kenney, B. (2014). The user is (still) not broken. Publishers Weekly. http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/libraries/article/60780-the-user-is-still-not-broken.html

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. (1897 – 1911). Sectional view of the seven tiers of stacks. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/26bfa330-c5b6-012f-4b03-58d385a7bc34

National Archives. (2025, September 22). Citizen archivist missions. https://www.archives.gov/citizen-archivist/missions

@robw

Livestreaming the Library slides

Livestreaming the Library slides