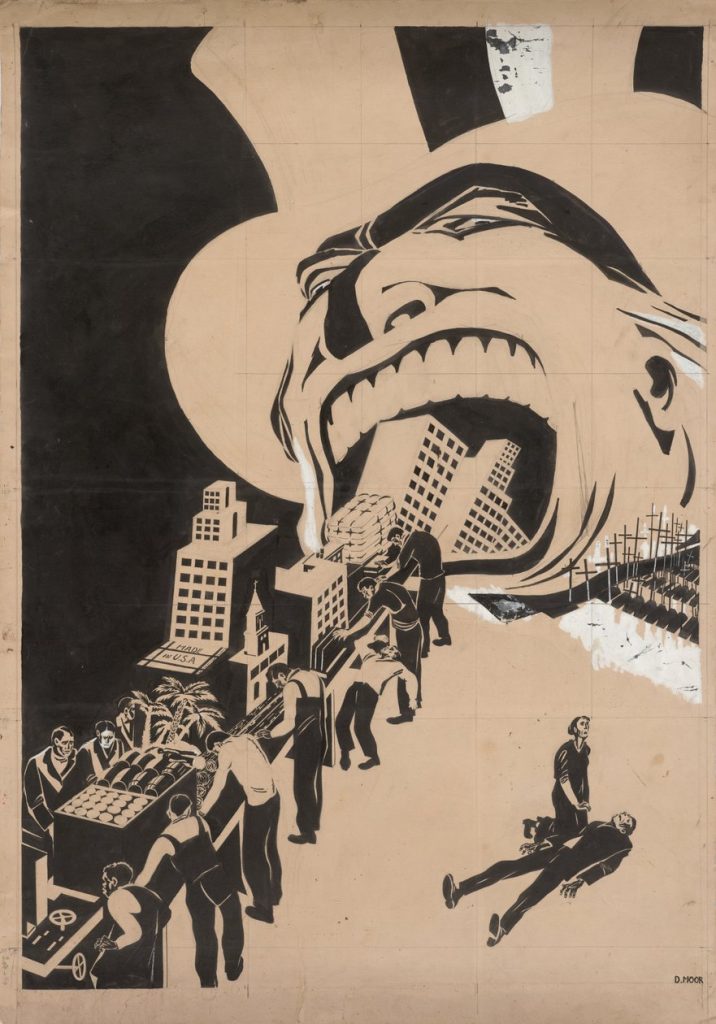

Russian samizdat (via)

Spinning off from what I touched on briefly in my Assignment X, I decided to dig deeper into the world and history of shadow libraries for my Wild Card post. Shadow libraries, as we discussed previously, are online troves of commercial books and scholarly texts made available digitally and for-free. Large sites like Library Genesis (LibGen), Z-Library and Anna’s Archive offer inconceivably large archives of literature, free to all, or at least free-to-all who are savvy enough to operate them (and also serve as lightning rods for a number of legal issues, as we will discuss later) while smaller, less visible, community-driven, thematically-specific libraries have emerged at a grassroots level, spread across Google Drives and the file sharing service Mega.nz, several of which popped up or prospered during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020.

In “The Genesis of Library Genesis: The Birth of a Global Scholarly Shadow Library,” the scholar Balázs Bodó (2018) traces the origins of both LibGen and the modern online shadow library model to the its roots in Soviet-era ideology, where the combination of state censorship, commercial scarcity, lax intellectual property laws and still widespread cultivation of literacy among the people created a unique piracy-contingent book distribution model. One LibGen admin described the Soviet era “samizdat” model to Bodó (p. 33) as such:

“People hoarded books: complete works of Pushkin, Tolstoy or Chekhov. You could not buy such things. So you had the idea that it is very important to hoard books. High-quality literary fiction, high-quality science textbooks and monographs, even biographies of famous people (writers, scientists, composers, etc.) were difficult to buy. You could not, as far as I remember, just go to a bookstore and buy complete works of Chekhov. It was published once and sold out and that’s it. Dostoyevsky used to be prohibited in the USSR, so that was even rarer. Lots of writers were prohibited, like Nabokov. Eventually Dostoyevsky was printed, but in very small numbers. And also there were scientists who wanted scientific books and also could not get them. Mathematics books, physics—very few books were published every year, you can’t compare this with the market in the U.S. Russian translations of classical monographs in mathematics were difficult to find.

So, in the USSR, everyone who had a good education shared the idea that hoarding books

was very, very important, and did just that. If someone had free access to a Xerox machine, they were [x]eroxing everything in sight. A friend of mine had an entire room full of [x]eroxed books.

These informal and physical networks rolled over naturally into the digital era, with BBS platforms like Fidonet, which hosted early collections via groups like SU.SF & F.FANDOM (which focused on Soviet sci-fi and fantasy literature), and lib.ru, a personal collection of Russian language texts founded in 1994 that eventually grew so large that it had to be splintered into a number of thematically specific collections, including LibGen, which focuses on scientific texts and still stands today as one of the largest and most infamous shadow libraries.

(In the name of both authenticity and being broke, I downloaded a .pdf of the collection in which this Bodó article appears from LibGen.)

Today the advantages of these libraries are numerous. They offer a truly democratized access to literature that would’ve been unimaginable in past generations, making texts freely available across class and global borders, offering alternative distribution routes for otherwise banned or censored books, and keeping rare or out-of-print texts in perpetual circulation. Understandably, these libraries are not without their critics and detractors. Publishers and authors alike have brought about numerous lawsuits against shadow libraries, arguing that the model infringes copyright and hurts their bottom line. (Creamer, 2023) while the FBI has “seized” the commercial book database Z-Library on more than one occasion (Javaid, 2022) but somehow it manages to reemerge (it’s still active right now).

Probably the most damning recent critique of shadow libraries stems from how their databases have been for generating AI models. It is alleged that Meta employees knowingly harvested 82TB of data from LibGen in training their AI, with stated intention to sidestep licensing this material from publishers and the express blessing of CEO Mark Zuckerberg (Reisner, 2025). This is the center of a large copyright infringement lawsuit brought by publishers against Meta, with the company arguing that it is “fair use” to mine this content for new material. It is a worst case scenario for advocates of these libraries, as it contradicts their implicit mission of liberating knowledge by reducing these great works of literature and research to mere data to be chewed up by the machines that are aiming to supplant the production of this type of work:

“LibGen and other such pirated libraries make information more accessible, allowing people to read original work without paying for it. Yet generative-AI companies such as Meta have gone a step further: Their goal is to absorb the work into profitable technology products that compete with the originals (Reisner, 2025).”

Bajaj & Bhateja (2022) are optimistic about court cases being brought against LibGen and Sci-Hub in India, suggesting that “the litigation should serve as a launching point to initiate a conversation on developing new business models in the publishing industry, the way Napster did for the music industry or Netflix did television (p. 26).” Though many have argued that the emergence of large scale legal digital distribution platforms Spotify and Netflix have had numerous negative effects on their respective industries, resulting in a homogenization of content (Svetkey, 2025), the underpayment of creators (Hsu, 2024), and, in the case of streaming music, an avalanche of exploitative AI-generated slop content (Lopatto, 2024). (Another advantage of free and copyright-indifferent platforms like shadow libraries is that they little financial incentive for users to flood them with the sort of meaningless generated slop and drivel that has begun to subsume the rest of the internet.)

Personally, I’m of the opposite belief. Rather than seeing the shadow library model hollowed out and repurposed to more commercial ends, I’d love to see copyright law reformed in a way that would decriminalize it. I’d love to see public and academic libraries integrate these crucial resources in their stacks “because what is known must be shared,” as per the OLCL slogan. Ironically enough, the OLCL is currently legal battle against Anna’s Archive, alleging that the Z-Library alternative scraped and shared their Worldcat database (Moody, 2024).

References:

Bajaj, R. & Bhateja, A. (2022). Bringing shadow libraries out of legal shadows: An opportunity for the Delhi High Court. Indian Journal of Law and Technology, 18(2). https://repository.nls.ac.in/ijlt/vol18/iss2/4/

Bodó, B. (2018). The genesis of Library Genesis: The birth of a global scholarly shadow library. In J. Karaganis (Ed.), Shadow libraries: Access to knowledge in global higher education (pp. 25-51). MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11339.001.0001

Creamer, E. (2023, September 15). Four large US publishers sue ‘shadow library’ for alleged copyright infringement. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/sep/15/four-large-us-publishers-sue-shadow-library-for-alleged-copyright-infringement

Hsu, Hua (2024, December 23). Is there any escape from the Spotify syndrome? The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/12/30/mood-machine-liz-pelly-book-review

Javaid, M. (2022, November 17). The FBI closed the book on Z-Library, and readers and authors clashed. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/11/17/fbi-takeover-zlibrary-booktok-impacted/

Lopatto, E. (2024, November 14). Not even Spotify is safe from AI Slop. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2024/11/14/24294995/spotify-ai-fake-albums-scam-distributors-metadata

Meyers, N. (2013, January 11). Shadow libraries: The dilemma. Book Scouter. https://bookscouter.com/blog/shadow-libraries/

Moody. (2024, September 23). OCLC Says ‘what is known must be shared,’ but is suing Anna’s Archive for sharing knowledge. Tech Dirt. https://www.techdirt.com/2024/09/23/oclc-says-what-is-known-must-be-shared-but-is-suing-annas-archive-for-sharing-knowledge/

Naprys, E. (2024, July 25). Biggest-ever leak of digital pirates: 10 million exposed by Z-Library copycat. Cybernews. https://cybernews.com/security/zlibrary-copycat-exposes-millions-digital-pirates/

Reisner, A. (2025, March 20). The unbelievable scale of AI’s pirated-books problem. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2025/03/libgen-meta-openai/682093/

Rumfitt, A. (2022, November 25). In defence of Z-Library and book piracy. Dazed. https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/57545/1/in-defence-of-piracy-and-z-library-shut-down-alison-rumfitt-writer-author

Svetkey, B. (2025, March 4). How streaming is making us all cinema-illiterate. The Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/streaming-impact-classic-fillms-algorithm-1236146209/

(via)

(via)