Category Archives: assignments

Inspiration Report: Library of Things

For my inspiration report I explored “libraries of things,” an emergent trend in which libraries lend out common household objects like tools, kitchen appliances, and sporting equipment. These programs not only serve to meet patrons’ basic day-to-day needs, they also reduce environmental waste and and even suggest a new model for a broader post-capitalist sharing-based economy.

For my inspiration report I explored “libraries of things,” an emergent trend in which libraries lend out common household objects like tools, kitchen appliances, and sporting equipment. These programs not only serve to meet patrons’ basic day-to-day needs, they also reduce environmental waste and and even suggest a new model for a broader post-capitalist sharing-based economy.

Click here to view the slideshow.

Reflection 2: Against AI

Luddites ludditing. (via)

As a card-carrying AI-skeptic I found it quite disappointing to read the Association of Research Library survey that reported an entirely neutral-to-positive opinion on generative technology among research librarians, with not one participant taking a negative position on the matter. (Lo & Vitale, 2023) It is shocking to me that so many information professionals take this technology so optimistically and uncritically when it is quite clear that the recent proliferation of large language models like ChatGPT has done more to muddle our information access than fortify it. Google results have gotten objectively worse since they’ve begun to implement this technology, both due to the company’s internal and sort of clunky “AI overview” function, which now frequently supersedes all human-generated search results (Titcomb, 2024) and due to the rapid proliferation of LLM-generated slop content that has just devoured the internet in recent years (Rogers, 2024). The slop wave has even found its way into public libraries already via ebook lending platforms like Hoopla (Maiberg, 2025).

And even if we put the sea of slop currently being created by LLMs to the side, if we take these tech goobers at good faith and assume that there will one day be a fully functioning version of this technology that doesn’t, for instance, recommend that people eat rocks daily (Titcom, 2024) what would that even offer us? A slightly more efficient reference encyclopedia? The fundamental conceptual flaw of LLMs logic is how it assumes truths lies in averages, that if you just chew up all of the information in the world you will find knowledge at its exact center. This is a depressingly STEM-centric way to think about the world, as if knowledge was a mere mathematical equation and not an intangible human phenomenon that sparks at the intersection of experience and understanding. Yes, you can get a rough encyclopedia-level overview of whales if you ask ChatGPT but if you want to understand whales, whaling and the overarching human condition that informs these things while also having a rich aesthetic experience you’re going to read Moby Dick. No matter how “accurate” these LLMs get they will never be able to synthesize the effect of a true genius/weirdo airing out their particular human obsessions. (This is part of the reason why visual AI art is consistently so boring [Jennings, 2024] and getting worse [Taxxon, 2024]. All the greatest creators in human history were outliers, not median-dwellers.)

I feel a real loss today when I Google whatever random cultural junk I am Googling and end up with a bunch of clearly ChatGPT generated blog posts, all written in the same wordy stilted prose designed to keep on page while saying as little as possible, all seemingly built by feeding off of one another. Fifteen or twenty years ago those same searches would’ve likely yielded a few passionate, experts sharing their knowledge in an interesting (if usually chaotic) fashion. Some of them might’ve even ended up being my friends (I would even prefer a living, breathing enemy over a robot at this point, too.) We need creative, obsessed, idiosyncratic human voices to foster information distribution, to convert facts into knowledge and build social infrastructure to cultivate wisdom.

And information degradation is just one of the many damning facets of these types of technology. I haven’t even addressed the environmental damage it is causing (Todorovic, 2024). Or the labor concerns (Demirici, 2024). Or the racism it propagates (Elliott, 2025).Or its potential for accelerating war profiteering (Brenes & Hartung, 2024). Or the fact that a lot of this magic tech is just mechanical turk-type sleight of hand exploiting third world workers (Vertesi, 2024). Or that it is likely making users dumber (Mihov, 2025).

This stuff is all bad and I don’t know why it doesn’t inspire more skepticism among library and information professionals. Especially now that some of the same tech robber barons who have spent the past few years cramming it down or throats are gutting our government towards an explicitly fascist end. I think conscientious librarians should be taking a hard line position against this technology instead of remaining ~cautiously optimistic~ about this clearly toxic technology in the name of cursed efficiency or out of fear of not seeming like luddites. (The original luddites were right, by the way [O’Shea, 2023].)

The only AI we respect, playing HORSE with a human-generated claymation model. (2004)

References:

Brenes M,. & Hartung, W. D. (2024, June 2). A.I. won’t transform war. It’ll only make venture capitalists richer. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/182145/ai-weapons-make-venture-capitalists-palantir-richer

Demirici, O., Hannane J. & Zhu X. (2024, November 11). Research: How gen AI is already impacting the labor market. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2024/11/research-how-gen-ai-is-already-impacting-the-labor-market

Elliott, F. (2025, March 4). It only took a day for LA Times’ new AI tool to sympathize with the KKK. SFGate. https://www.sfgate.com/la/article/la-times-ai-tool-sympathizes-kkk-20202315.php

Jennings, R. (2024, May 23). Why AI art will always kind of suck. Vox. https://www.vox.com/culture/351041/ai-art-chatgpt-dall-e-sora-suno-human-creativity

Lo, L. S. & Vitale, C. H. (2023 May 9). Quick Poll Results: ARL Member Representatives on Generative AI in Libraries. Association of Research Libraries. https://www.arl.org/blog/quick-poll-results-arl-member-representatives-on-generative-ai-in-libraries/

Maiberg, E. (2025, February 4). AI generated slop is already in your public library. 404 Media. https://www.404media.co/ai-generated-slop-is-already-in-your-public-library-3/

Mihov, D. (2025, February 11). AI is making you dumber, Microsoft researchers say. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/dimitarmixmihov/2025/02/11/ai-is-making-you-dumber-microsoft-researchers-say/

O’Shea D. T. (2023, July 10). The Luddites were onto something. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2023/07/luddites-machine-breaking-capitalism-technology-climate-change

Rogers, R. (2024, July 2). Google search ranks AI spam over original reporting in news results. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/google-search-ai-spam-original-reporting-news-results/

Taxxon, P. (2024, June 1). Untitled [Tumblr Post]. Retreived from https://patricia-taxxon.tumblr.com/post/753935866543702016/this-is-on-openais-official-demonstration-and-it

Titcomb, J. (2024, May 28). How Google’s malfunctioning AI risks ruining the internet. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2024/05/28/google-malfunctioning-ai-risks-ruining-internet/

Todorovic, I. (2024, September 4). ChatGPT consumes enough power in one year to charge over three million electric cars. Balkan Green Energy News. https://balkangreenenergynews.com/chatgpt-consumes-enough-power-in-one-year-to-charge-over-three-million-electric-cars/

Vertesi, J. (2024, April 4) Don’t be fooled: Much “AI” is just outsourcing, redux. Tech Policy. https://www.techpolicy.press/dont-be-fooled-much-ai-is-just-outsourcing-redux/

Assignment X – Digital Citizen Archivists and the Participatory Library

DIY History Site (University of Iowa Libraries)

One thing that stood out to me in learning about Participatory Libraries in Module 4 was the University of Iowa Library’s DIY History site, a crowdsourced project calling on community members to help accelerate their digitization efforts by transcribing and tagging collection items (University of Iowa Libraries, n.d.). What stood out to me about this project is how directly it involves the public in the archival process with participants essentially learning to be librarians and archivists themselves. This is an essential skillset in an age when any serious information consumer is already working as something of a librarian. As Hadi & Gerson (2023) put it, “the internet has allowed archives to become something that can be created and preserved, collectively. Online, everything is archived, and everyone is an archivist.”

Some of the most useful online resources come from crowdsourced and/or DIY efforts. These include old standards like Wikipedia and the Internet Archive but also less-visible ones – “shadow libraries” like Z-Library and Anna’s Archive which offer enormous free collections of academic pdfs and commercial ebooks (Meyers, 2013) or torrent communities like the film archive Karagarga, which has long been a strong preservationist force against the ephemerality of commercial streaming services (“Karagarga,” 2015). One my favorite DIY archival models in this mold to have emerged in music communities recently are artist-based “trackers“, sprawling, shared Google sheets that attempt to comprehensively trace the complete recorded output of popular and cult musicians alike, documenting otherwise unattainable music (fan leaks, Instagram snippets) and other mixed media content, often dating back to the artists’ pre-fame years. (TrackerHub, n.d.)

Playboi Carti Tracker (Google Sheets)

There are few obvious problems with these types of DIY archives, though. The biggest of these is a matter of legality – more often than not these fans obviously do not have any right to duplicate or distribute this media. The Internet Archive, for instance, has been on the losing end of a high profile copyright case brought by book publishers (Knibbs, 2024). But also there are often issues with preservation, searchability, accessibility and (especially) fidelity. I can’t tell you how often I look at Instagram and see a would-be mind blowing historical photograph except it was digitized via an iPhone photo taken at a weird angle, riddled with lens flare.

In her 2011 meme/manifesto, “The User Is Not Broken,” library blogger K.G. Schneider (2006) notes “The OPAC is not the sun. The OPAC is at best a distant planet, every year moving farther from the orbit of its solar system,” but I wonder if these emerging information networks even constitute the same galaxy anymore. It’s hard to imagine any formal library inquiry that would lead a patron to the Playboi Carti Tracker. Nor is it likely that the average Playboi Carti Tracker-contributor would be consulting a formal library in their research or process. So my question then is how can we bridge these two universes? On one hand you have a mass of civilians who are intuitively doing essential archival work and on the other libraries that could potentially offer the exact sort of technical and institutional support that these armchair archivists are often lacking. I’d love to see a library program that could somehow integrate these more fringe digital resources into their existing databases or one that could help to put their creators on a path towards acquiring proper legal clearances for this type of work. (The intellectual property anarchist in my heart dreams of a traditional library system that is completely unmoored from copyright law but sadly I don’t think that will ever become a reality.)

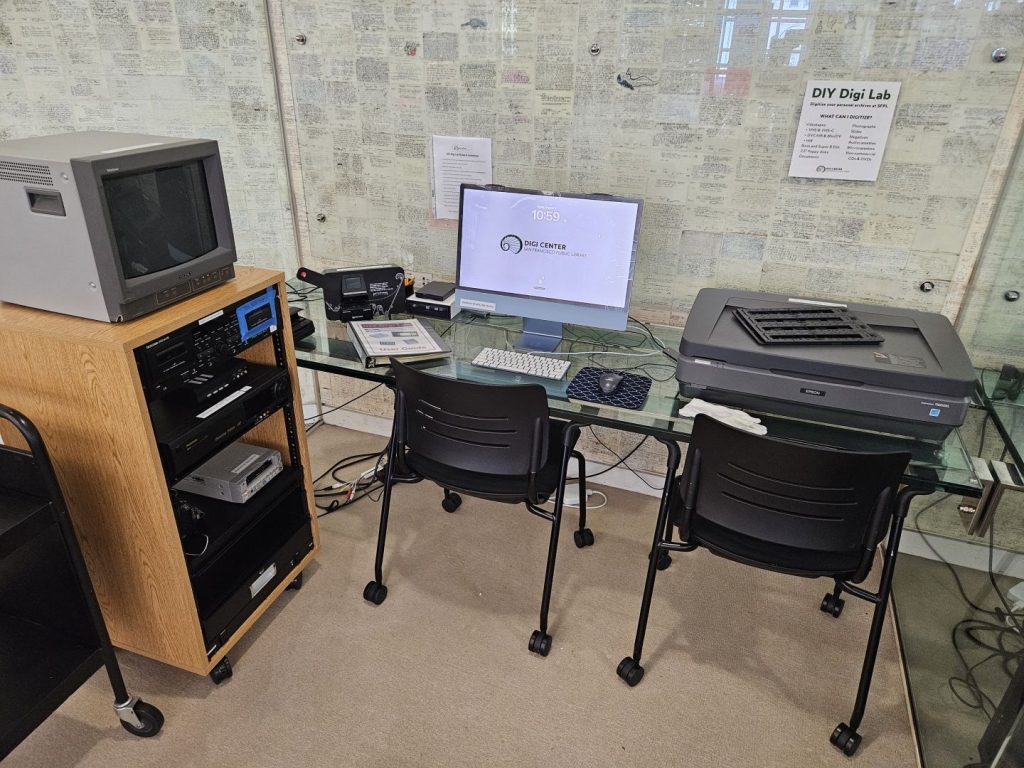

One interesting development in this direction has been the rise of Memory Labs, library makerspaces dedicated to democratizing the archival process. Public libraries in places like San Diego and Los Angeles provide studios where community members can access scanners, 360-degree cameras and other digitization technology to preserve their own personal histories (Bhatia, 2024). Most of the Memory Lab conversation seems focused on analog-to-digital conversions but I wonder if these labs could expand to also encourage the preservation of born-digital content and give the citizen archivists of the internet better means to properly encode, organize, preserve, and disseminate their efforts.

DIY Digi Lab (San Francisco Public Library)

DIY Digi Lab (San Francisco Public Library)

References:

Bhatia, J. (2024, October 2). At the library, in the lab, saving history. Mellon Foundation. https://www.mellon.org/article/at-the-library-in-the-lab-saving-history

Hadi, R. & Gerson. (2023, April 25). Why community archives are a radical approach to archiving. Scratching The Surface. https://scratchingthesurface.fm/stories/2023-4-25-community-archives/

Karagarga and the vulnerability of obscure films. (2015, July 3). National Post. https://nationalpost.com/entertainment/weekend-post/karagarga-and-the-vulnerability-of-obscure-films#

Knibbs, K. (2024, September 4). The Internet Archive loses its appeal of a major copyright case. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/internet-archive-loses-hachette-books-case-appeal/

Meyers, N. (2013, January 11). Shadow libraries: The dilemma. Book Scouter. https://bookscouter.com/blog/shadow-libraries/

Schnieder, K.G. (2006, June 3). The user is not broken: A meme masquerading as a manifesto. Free Range Librarian. https://freerangelibrarian.com/2006/06/03/the-user-is-not-broken-a-meme-masquerading-as-a-manifesto/

University of Iowa Libraries. (n.d.). DIY history – about. Retrieved Februray 13, 2025 from https://diyhistory.lib.uiowa.edu/about-the-project

Wallace, K. (2020, May 15). Sharing stories: LA Covid-19 community archive. Los Angeles Public Library Blog. https://www.lapl.org/collections-resources/blogs/lapl/sharing-stories-safer-home-archive