For my innovation roadmap and strategy project, I explored repair cafés — community events where skilled volunteers help people repair broken items of all kinds. Here’s the PDF!

For my innovation roadmap and strategy project, I explored repair cafés — community events where skilled volunteers help people repair broken items of all kinds. Here’s the PDF!

And so this class comes to an end. It’s been a whirlwind of a semester, but everyone in this class has been a pleasure to learn from! I did my virtual symposium on five key takeaways I got from this class. Here’s a PDF, just in case the pictures don’t show up.

I did my Inspiration Report on facilitating generative AI use in libraries (in the Boston Public Library in particular) because I know that AI is changing how we create, use, and consume information, and libraries will be an important part of ensuring that we learn how to adapt to that new information environment well.

Here’s the link to the PDF, if for some reason the pictures don’t show up.

I’ve loved libraries as long as I can remember. I practically grew up in them, bringing home stacks of books from our weekly library trips when I was small, using them as a relaxing place to hang out after school and do homework with friends in high school. I knew I liked their general ethos — free knowledge and entertainment for all. But I hadn’t thought particularly deeply about how they fit into the larger social order until I picked up Eric Klinenberg’s Palaces for the People at the beginning of 2020.

That year was, of course, practically an enormous case study in the importance of community and togetherness. At the time, though, it was only January, and COVID-19 hardly on my radar, nothing but a few worrying news articles on a far away disaster. I had no idea of the new significance the ideas in the book would have for me just a few short months later.

Klinenberg’s main thesis in the book is the importance of “social infrustructure”, or “the physical places and organizations that shape the way people interact” (Klinenberg, 2018, p. 4). Particularly, he focuses on how we can use these places and organizations to build the kind of community in which people trust each other, check on each other, and support each other. Even as simply a place to gather, libraries function as pillars of social infrastructure on which we can build our communities.

Libraries have a history of providing support during emergencies, acting as distribution centers for food and emergency supplies and providing a source of wifi and power when it was scarce, in addition to performing their normal function as information hubs, which is especially critical in a crisis (Hagar, 2014). During COVID lockdowns, libraries all over stepped up to support their communities. Of course, they adapted their basic circulation services to function in the new socially-distanced normal and worked to provide coherent information about the virus amid a tide of misinformation. But they also updated their physical infrastructures to extend their wifi outside their buildings, providing access to the crucial service even when they couldn’t be open. They created storytime and craft kits for parents to take home to their children to help keep them occupied during the long hours at home. They ran virtual programs on Zoom to help keep the community connected.

If you’re used to thinking of libraries as book warehouses, some of these things might seem a bit out of scope, but connecting people to information (and other resources) they need translates to serving people in all kinds of ways. With specialized resources for immigrants, job seekers, entrepreneurs, adult learners, and more, libraries are “skill[ed] at reaching populations others miss” (Mattern, 2014). Having a place to go when you need help and don’t know where to start is incredibly useful. But Klinenberg highlights a few community programs that seem to be much less targeted to providing information. A virtual bowling league brings together people from different library branches in the spirit of friendly competition. A new mother finds a place outside her home that welcomes her and her young child, and meets others that share her situation. These parts of library service are about connecting people to each other, because the biggest resources of a community are its members.

I didn’t use the library for anything other than e-books during the COVID lockdowns. But as the long months of isolation brought the importance of community into sharp focus, I thought a lot about the tools we use to build it. Good libraries have the potential to be some of the best.

Hagar, C. (2014). The US Public Library Response to Natural Disasters: A Whole Community Approach. World Libraries, 21(1). https://worldlibraries.dom.edu/index.php/worldlib/article/view/548/472

Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life. Broadway Books.

Mattern, S. (2014, June). Library as Infrastructure. Places Journal. https://placesjournal.org/article/library-as-infrastructure/

When I was in high school and trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life, my main criteria was that I wanted to be in a field in which I would always be learning. Of course, things in the world change so much that that’s true of almost any field, but it’s particularly important for libraries. Libraries are information centers, and in order to do the best job at educating and informing the public, we need to make sure we are educated ourselves, and at the rate the information landscape is changing today, that requires constant learning.

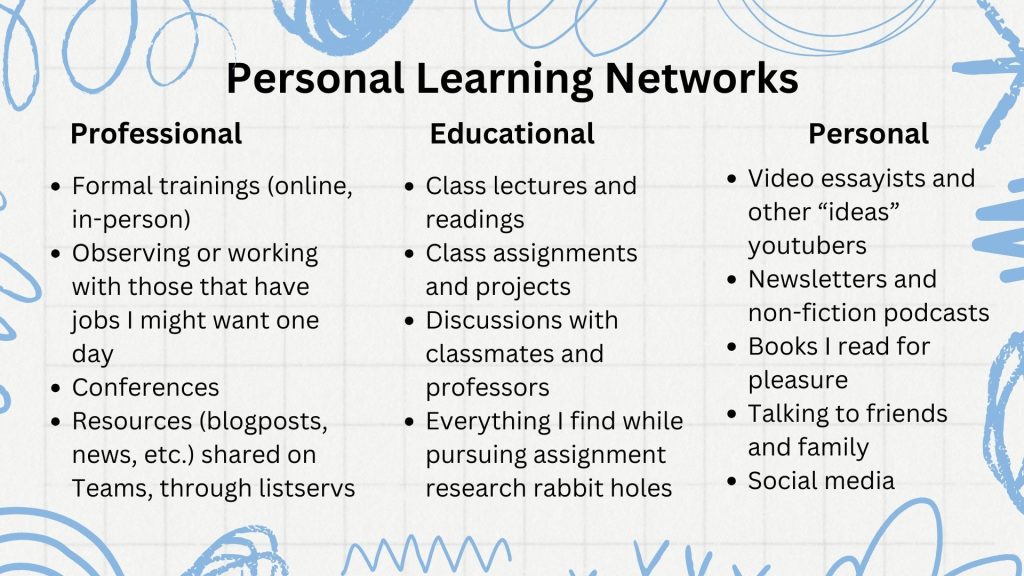

I’m intrigued by the concept of personal learning networks, so I took a second to map out my own.

One of the things I have found most important for myself is to curate my various feeds so that my passive media time — the time I spend watching YouTube videos or scrolling through social media or even checking my email — ends with me learning about something I’ve been interested in.

When it comes to the more formal kind of professional development, like trainings provided by the library, conferences, or even things like committees and work groups dedicated to solving a specific problem that are open to employees of all levels and job titles, I’ve found that, unfortunately, access isn’t everything. In her blog post “Library as a Classroom for Library Staff”, Sally Pewhairangi notes that the people who have the most trouble finding time for “upskilling” are part-time, front-facing staff, and she creates some 60 minute online trainings directed specifically towards time-crunched employees. While access to online trainings is absolutely something to strive for, management still must work to provide time — even if it’s just an hour — for their staff to dedicate to learning.

Self-directed learning on the part of library employees is important, but the only way it works is if management enables it by providing them with enough time — which sometimes means more than barebones staffing — to do so. I’ve often been frustrated at the library where I work when the training team puts forth interesting trainings on topics I’ve been curious about, only to find that we simply do not have the time or the staffing for me to be off-desk. It’s important for every level of management to consider this, whether it’s direct supervisors advocating for their direct reports to have dedicated time for learning, upper level management designating it as a priority system wide, or those who do the hiring taking it into account when deciding proper staffing levels.

Organizational structure can also play a role in professional development. If employees are allowed, or even encouraged, to go beyond their job descriptions to follow their interests, they can develop skills they never would have been able to if they were confined to their specific role. As Michael Stephens says in The Heart of Librarianship (p. 27),

“What we do is not simply what is written in our job descriptions. I’ve never known anyone who worked in a library who didn’t, often, stray far and wide from the tasks they were hired to do. We cannot afford siloed mind-sets. We go where we are needed and do what is necessary to serve those who come to us.”

Pewhairangi, S. (2016). Library as a Classroom for Library Staff.

Stephens, Michael. (2016). The Heart of Librarianship.

Stories are powerful things. They are, of course, part of the lifeblood of any public library. We use stories both to find people like us, to recognize our own experiences in others and to feel validated and less alone, and to experience lives we would never have gotten to live through the eyes of others, to find connections even with those most different from us. This is why having diverse collections is so important — we want as many people as possible to see themselves reflected in the library, and we want to give people the opportunity to learn more about as many different kinds of people as possible. When you’ve seen things from another person’s perspective, it’s a lot easier to see them as a person. This is becoming more and more important in today’s increasingly divided world. Providing access to stories of all kinds is beneficial at a societal level, and, together with providing access to reliable information, is one of the prime directives of public libraries everywhere.

Since stories play such an important role in our lives, I’ve loved seeing libraries taking curation of stories to another level by collecting and sharing patron stories, or working with organizations like the Human Library to help their patrons connect with people with different experiences. The Boston Public Library system, where I work, has had a few programs that encourage people to tell their stories.

We have circulating oral history backpacks — kits with high quality, portable recording equipment and a binder with guidelines on the kinds of questions to ask to encourage people to tell their stories — so patrons can record their family histories, interview their neighbors, or even complete more complex oral history projects. Patrons can keep the stories for themselves, or, with permission from the storytellers, can work with the library to find an oral history repository to donate copies to.

This year, the BPL also worked with GrubStreet, Boston’s creative writing center, to offer workshops all around the system on personal storytelling. The stories created in those workshops were then published in a community anthology that we’ve added to our local history collections, along with similar publications from workshops in years past.

When exploring the various community anthologies the BPL has created, I came across Faces of Dudley, a book featuring oversized photographic portraits of residents of Dudley (now Nubian) Square in Roxbury that were part of a temporary installation on the outside of the Roxbury Branch Library in 2015. It would be amazing to see the library make creating installations like this a regular thing cycling through the different neighborhoods. It would make a great way for residents to come together to tell their stories.

It’s easy for people who haven’t stepped into a library in the last few decades to think of them as book warehouses, but any more regular user knows they are so much more. A big part of that is the library spaces themselves. As Michael Agresta discusses in his 2014 article for Slate, What Will Become of the Library?, many libraries have been moving some of their stacks off-site to focus more on becoming “third-places” where people can gather outside of their homes or workplaces.

The Boston Public Library system, where I work, is one of them. They’ve modernized the Central library and many of their branches as each has been renovated, including new spaces that invite new kinds of interaction. The Central Library an iconic building with ornate architecture and murals by John Singer Sargent, now also includes a makerspace with a 3D printer, Adobe Creative Suite, and the InnoLAB, a studio with a greenscreen, camera, and audio equipment where patrons can make videos and podcasts.

When the Roxbury branch completed its renovation in 2020, it was equipped with the Nutrition Lab, a professional kitchen that hosts cooking workshops that celebrate the myriad cultures that make up the surrounding community while helping patrons develop nutritional literacy and cooking skills. Next week alone, they have programs teaching how to prepare savory and sweet plantains, Irish Colcannon croquettes and Boxty Tacos, and a one-pot meal based on sofrito.

While these flashy additions are definitely amazing, they are really only feasible at the Central library or branches that have more space. However, a lot of thought can be put into smaller branches as well to create spaces that work for everyone. For instance, my branch in Roslindale, which completed renovation in 2021, is very small, with a single floor that can be seen in its entirety from the central circular combination circulation/reference desk. To make it more of a community space while trying to meet patrons’ sometimes conflicting needs, we have a sound insulated quiet reading room for those seeking the more traditional library experience, while the main floor is typically more lively, allowing people to work together and socialize at a normal volume.

Of course, there are ways to make the library more welcoming that don’t require a renovation. Like the Berkeley library in 2018, the Boston public library recently rolled out a limited library card called a Welcome Card that doesn’t require patrons to show proof of address or even a photo ID. So far, I’ve offered these cards to some frequent patrons experiencing housing insecurity who hadn’t been able to get a library card before, as well as to new immigrants who didn’t yet have a permanent place to live. It has been a great way to show that these patrons were as welcome here as any other.

Agresta, M. (2014). What Will Become of the Library?

Rees, M. (2018). No Permanent address? No Problem. Berkeley Library makes it easier for those without homes to get library cards

There have been a few information revolutions in the long arc of human history, from the printing press to the radio to the internet. Generative AI, which allows users to generate fully developed content with just a few words, may be the next in that list. After the explosive growth of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT and Claude and image generators like DALL-E and Midjourney over the past few years, as well as models that create video (Sora), music (Suno), and even podcasts (NotebookLM), it’s hard to deny. Even if you never seek out the tools yourself, they have been integrated into our daily lives. Most Google search results pages are topped with an AI summary, and if you use Windows 11, Microsoft’s Copilot has been integrated into the operating system.

More worryingly, AI-generated output has proliferated on the internet. In a world where it is pretty trivial for a tech-savvy someone to set up a social media account that replies to people using an LLM, it can be hard to tell if the person responding to you is actually a human. Because image generators can create not only stylized art but also photorealistic images, it is easier than it ever has been to create things that look real, but aren’t. While most complex video generation is still pretty obviously AI-looking, at the current breakneck pace of progress, it might not be too long before it will be difficult to trust videos as well.

All of this adds up to an extremely treacherous information landscape. How do you know what’s credible when so many things can be generated at the drop of a hat? Libraries, as information institutions, have a responsibility to at the very least stay abreast of developments in this area.

AI can of course be an incredible tool, and libraries can run programs to help their patrons use it to their advantage. For example, academic libraries can run workshops on how to use LLMs as a personal tutor, including information on best practices for double-checking the information it provides. English as a second language teachers can, as part of their curriculum, teach students how to use LLMs as a conversation partner that can correct their grammar and teach new vocabulary in real time.

However, libraries, particularly any staff who do research, must be aware of the traps created both by directly using LLMs to find information and by the prevalence of AI-generated content online, and must do their best to pass these insights on to patrons. Perhaps we can do this through specific AI literacy programming that goes into depth about how you might be able to recognize AI-generated content, or how to double check information it generates. Perhaps we can do this in a more playful way by incorporating that AI literacy into more fun programs that use the tool. However we do it, it is imperative that libraries remain a source of unbiased, reliable information in the minds of our patrons.

When I started my first library job in 2022, one of the main things I noticed was the sense of community that sprung up almost immediately. To be fair, that was why I’d changed careers in the first place — coming off a few years of pandemic-induced isolation in an industry that didn’t feel connected to anything, I wanted to feel like I was doing something that was helping someone. Even as a newbie in what Michael Stephens calls “the ultimate service profession”, that’s exactly what I was doing. Things started small, of course. I helped people check books in and out, helped them navigate the stacks and the library website and the ever-frustrating printers. But as time went by, those little interactions started to build relationships. Patrons would see me outside of the library, and say hi. We’d get into little conversations about everything and nothing. Eventually, some patrons felt comfortable enough to ask for more complex things, like help calling the electric company to understand a bill, or finding a lawyer who specialized in estate law.

While I was building up those relationships myself, I saw the same thing happening between patrons who, without the library, otherwise never would have met. Caregivers in the children’s area would trade childcare tips and recommendations for nearby services as their children played together, then, upon discovering that they lived quite near each other, would arrange play dates outside the library. A new member of the knitting and crochet group who was new to the craft would join, learn from existing members, and in a few months would be teaching new members herself. A senior who came in every morning to read the newspaper, upon learning that we had weekly movies in the afternoons, would join one, and then become a founding member of a cribbage club with others he’d met there.

I think this network of relationships, this fertile ground for new connections, as is least in part what David R. Lenkes (as quoted by Sally Pewrainangi) meant when he said that “libraries are infrastructure of the community”, that they are “part of a powerful platform that enables our communities to succeed”. Using a welcoming environment to build trust, libraries can provide a place where not only library staff help the patrons by providing them with reliable information and robust services, but patrons can help each other simply by getting to know each other. In other words, by building community.

Pewrainangi, S. (2014). A beautiful obsession.

Stephens, Michael. (2016). The Heart of Librarianship.