Traditional notions of reference practices and knowledge acquisition in libraries are now upended by the Internet and evolving technologies. The lofty idealized interactions––receiving an articulated information need from a patron, using physical and digital libraries resources to locate high-quality material that most effectively addresses the need, resulting in a satisfied patron equipped with new knowledge––are complicated by the freedom of online searching offered to people by sites like Google, coupled with the increasing presence of AI as a retrieval tool and an information ‘source.’ This has led to anxiety in many libraries about how to deliver meaningful service to users.

Ten years ago, Brian Kenney noted an interesting trend: “even as traditional reference transactions continue to decline, the use of our building is surging, increasing about 20% each year” (2015). This remains true, as I write this from a table at the public library, where patrons surround me watching videos on computers, looking for books on the shelves, writing notes on paper, chatting with friends, and eating [gasp] lunch with their families. There may not be a queue for research questions at the librarian’s desk, but the building is full of people who deeply value the space. This leads us, as information professionals, to reflect upon what our users want from us and how we can proactively meet their needs, desires, and dreams.

As I sat down at this table, two people at the table next to me were gathering their things. They were different ages, I would guess one of them was a young adult and the other was about 40 years old. They were chatting and packing up what looked like the parts of a PC computer that they were in the process of building themselves. I figured they were friends, relatives, or somehow acquaintances. When they were leaving, passing by my table, I heard them within earshot exchanging names and “it’s nice to meet you.” Two different patrons of two different generations, connected by a common project inside the library.

This is how community members are organically using library spaces, and it is imperative that librarians offer renewed support for such prospects. In essence, patrons “want help doing things, rather than [just] finding things” (Kenney, 2015). Rather than waiting for isolated reference request transactions where librarians are completing a majority of the task at hand, we can find ways to use our expertise to assist, educate, and empower our users’ abilities to pursue new learning experiences.

How does this look different from a community center or a class at a local community college? Libraries are uniquely positioned to promote and facilitate informal learning and skill shares within comfortable, safe spaces backed by access to the tools required to follow a curiosity or navigate the changing world (Stephens, 2025). Many of these needs, desires, and dreams involve proficiency in technology. As opposed to holding out for the return of now-antiquated services, library staff can prepare for and shape the future value of their offerings.

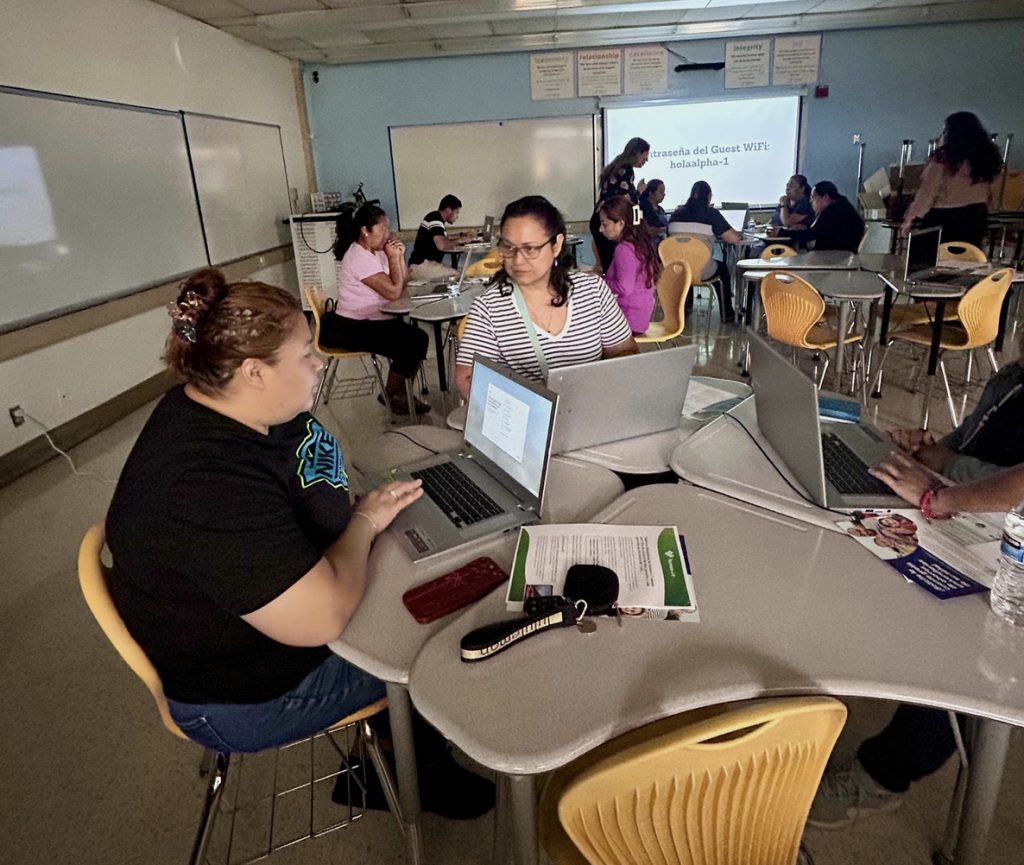

Willing staff who are wondering what this could look like, can look to the community for inspiration. Recently, the Hispanic Foundation of Silicon Valley partnered with a non-profit called Everyone On to provide parents from a local grade school with laptops and 4 weeks of computer skill training aimed at helping caretakers “engage in their children’s education by confidently navigating the digital world” (Hispanic Foundation of Silicon Valley, 2025). Workshops of a similar model could effectively be adapted into library programming, where users learn relevant skills that address an identified need or interest, in community. Library service in the future requires us to serve users by helping them serve themselves and one another. Connections are already happening, the future is now, and it can all happen inside the library.

Reference

Hispanic Foundation of Silicon Valley [@hispanicfoundationsv]. (2025, July 25). Yesterday, HFSV welcomed a new group of parents at @alpha_public_schools José Hernández School, to our #DigitalLiteracy program [Photograph]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/DMeFiTIy7u2/

Kenney, B. (2015, September 11). Where reference fits in the modern library. Publishers Weekly. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/libraries/article/68019-for-future-reference.html

Stephens, M. (2025). Hyperlinked library: Learning everywhere [Lecture video]. SJSU. https://sjsu-ischool.hosted.panopto.com/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=012f4ddc-7161-407c-b277-af34011b768c